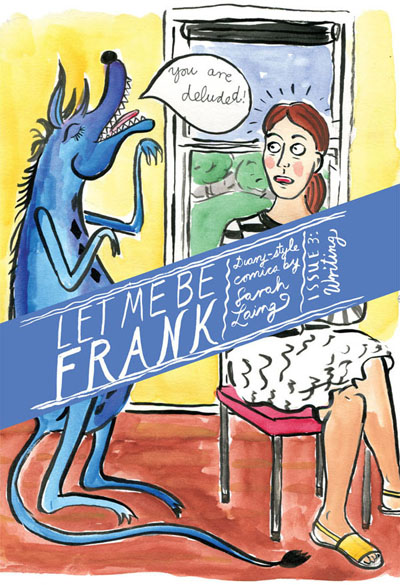

Sarah Laing

Matt Emery: What has been challenging about assembling this project so far?

Rae Fenton: The greatest challenge for me has been the lack of a one-stop shop for contacts, as I mentioned earlier, but this just tells me how needed Three Words is; this will be, to the best of my knowledge, the first anthology of its kind for women comics artist and cartoonists in New Zealand, and will, I hope, also function as a beginners' directory, if not a definitive one. I'd like to see New Zealand's women cartoonists, comic artists and graphic novelists in books like Graphic Women, by Hilary L. Chute, for example. But a lot of NZ comics artists seem happy to remain underground, which is fine, but I think history has shown us how underground can be a synonym for buried. Accounting for everyone may prove our greatest challenge overall.

Matt Emery: Indira, there was a wonderful phrase you used in a facebook comment to describe what you disliked about a portion of the NZ comics community/scene that I can't for the life of me find or recall specifically but I thought it a very astute observation at the time. Do know what I'm talking about? Can you elaborate on my vagueness?

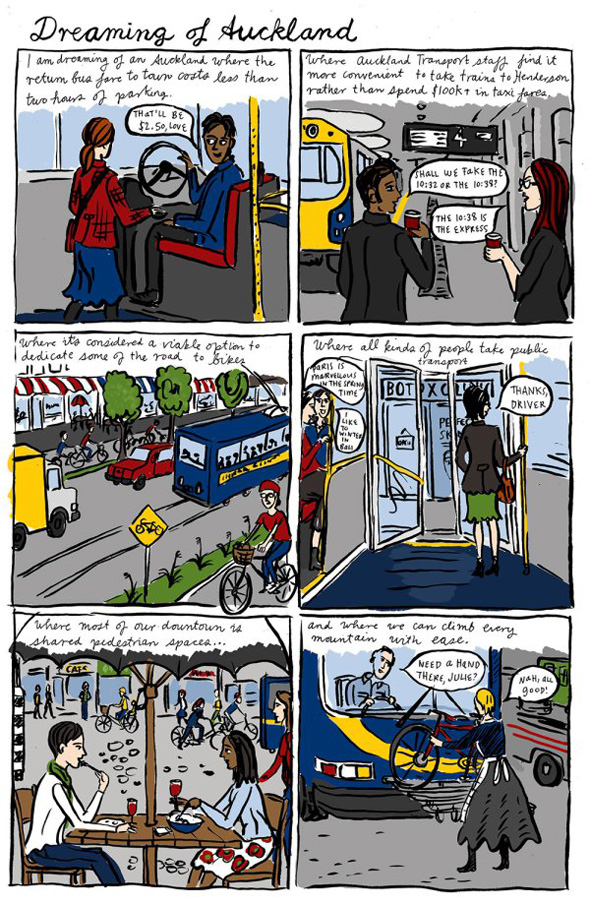

Indira Neville: Heh. I can’t recall the exact words but it would have been one of my standard rants about the idea of ‘competent boy comics’. ‘Competent boy comics’ is a term I use to describe the current high profile and related proliferation of a certain kind of comic in New Zealand. In my opinion, these comics share a number of characteristics - a very proficient drawing style, a tasteful colour palette, a commitment to traditional linear narratives, page layouts and frames, and an adherence to the conventions of whatever genre the artist is working in (usually adventure/action and/or fantasy and/or slice-of-life/biographical). They essentially have a kind of ‘professional’ inoffensive smoothness and adequate appeal. It’s also important to note that ‘competent boy comics’ aren’t only made by boys, in this context I think of ‘boy’ as an adjective rather than a noun.

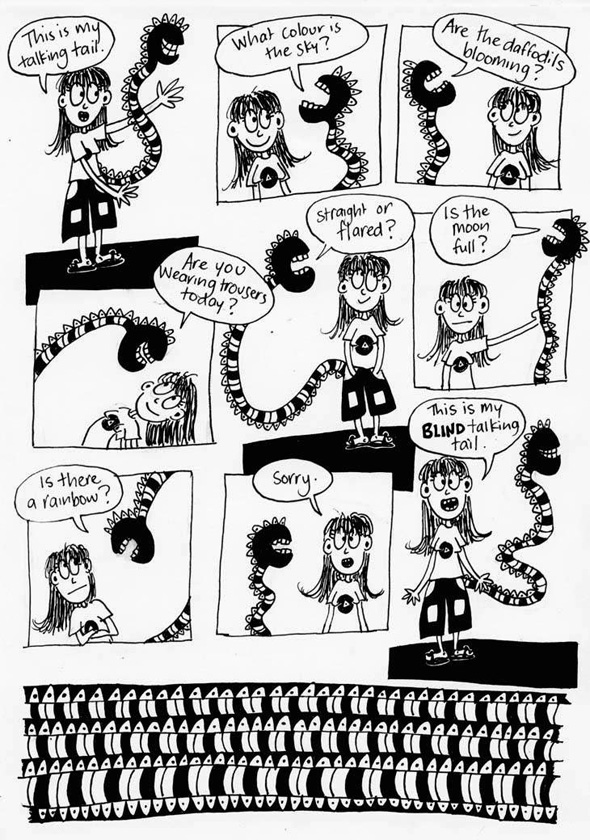

I have a couple of thoughts about ‘competent boy comics’ – the first is that they are just not my cup of tea. Some examples are blander than others, but I actually really struggle to see any of these comics properly, they all look pretty much the same to me and my eyes just slide off the page. They seem to me to eliminate all the things that make the medium of comics amazing – the weirdness, the silliness, the mess, the horror, the confusion, the spazziness, the raw, the personal, the grubbiness, the joy and the home-made.

I accept however, that what I have just described is simply a matter of taste, and that these kinds of comics can still be valid even if I don’t personally like them. My second point however is that, while the works themselves may be valid, the discourse around them isn’t (to be fair this doesn't necessarily come from the artists) and it really pisses me off! Essentially it seems to me that many people do not recognise ‘competent boy comics’ as just one way of approaching the medium. Instead these works are represented via the obliviously offensive notion of a comics ‘maturity’ or ‘pinnacle’, as if they are ‘better’ and something for other kinds of comic artists to aspire to – yuck!

This idea was acutely illustrated for me when one prominent New Zealand comics personality publicly compared the ‘progress’ of New Zealand comics with that of the Dunedin music scene. As I remember it, he essentially talked about how making comics was kind of an underground DIY activity like music in the early years of Flying Nun, but that now, like Flying Nun, comics are widespread and professional and accessible and commercially viable. For me this analogy has two main flaws – firstly the DIY music scene didn’t stop just because Flying Nun became a ‘proper’ record label; and secondly, when Flying Nun did go all respectable we had to listen to a lot of really shit bands (remember Garageland and Superette!?)