by Jane Thompsen, originally appeared in School Journal, 1984, Part 4, number 2.

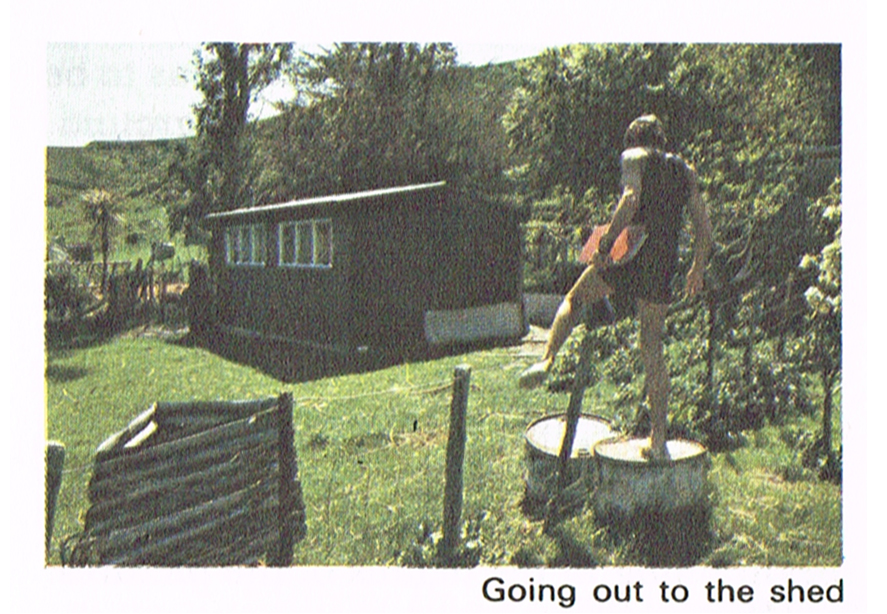

AT NINE O'CLOCK every morning, from Monday to Thursday, Murray Ball goes to a quiet place to think of ideas for his cartoons.

He might go to the top of a hill near his house, or under a tree in the garden. It has to be somewhere he won't be disturbed—because he needs to sit down, make himself comfortable, and go into a kind of a dream. It is almost like going through a door, shutting it behind him and finding himself in another world—the topsy-turvy world of Footrot Flats.

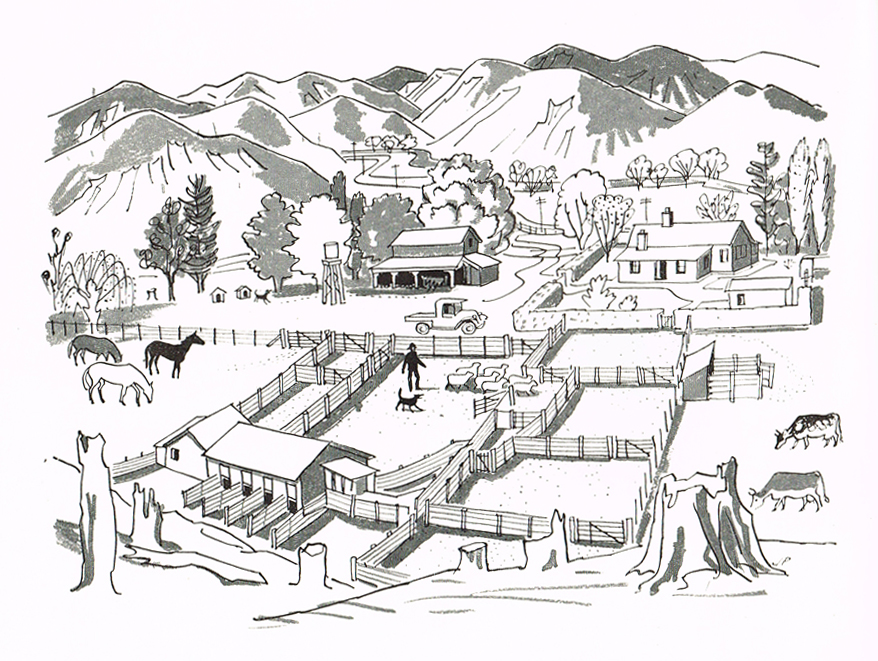

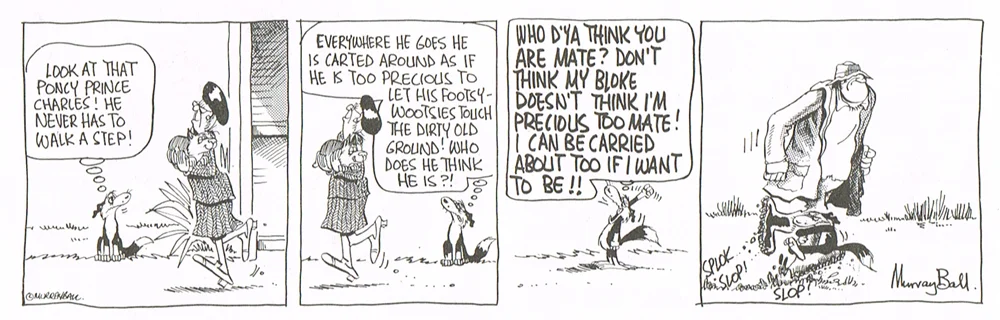

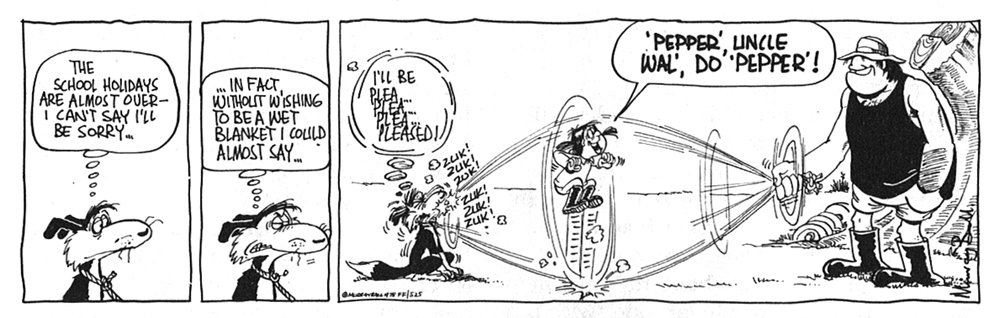

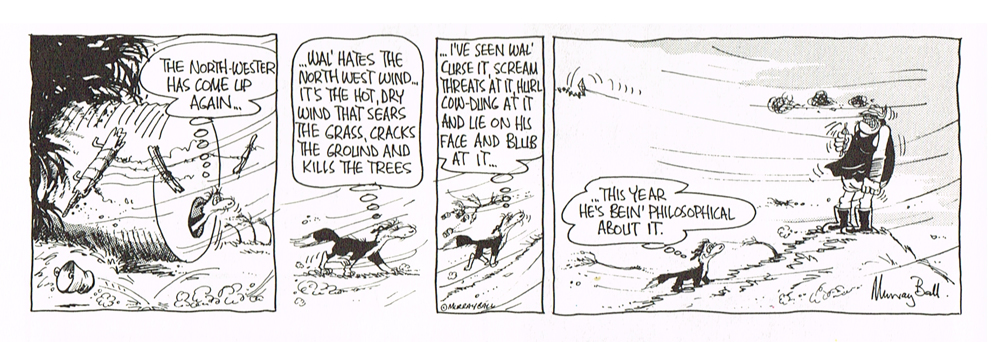

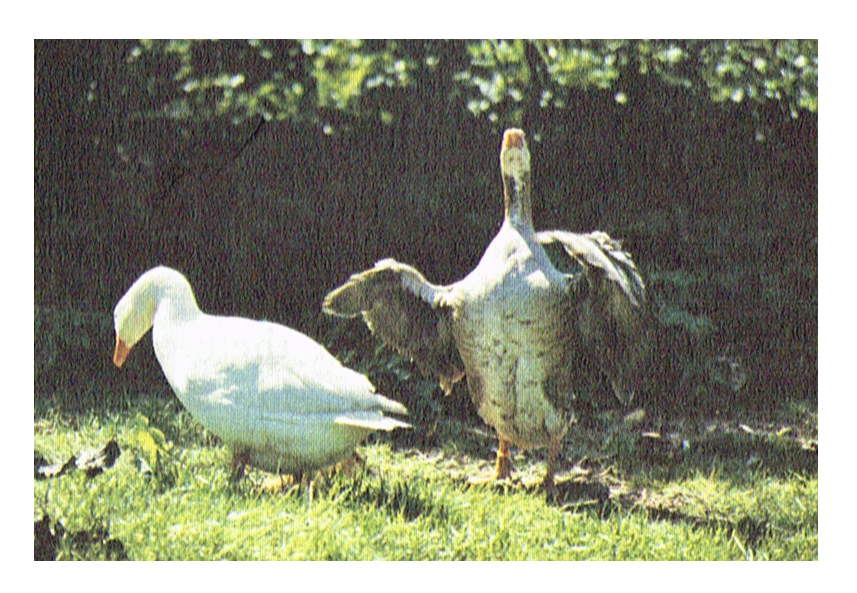

Many characters whom he knows very well live in that world. There's Wal, a farmer, thoughtless and dour and mean, who also has some good qualities—he would never do anything dishonest. There's his dog, who adores him and would do anything for him, although he tends to be rather greedy and jealous. There's Gooch, a much more sensitive farmer, who even tries to protect pests such as blackberry and possums. There's fussy Aunt Dolly, who tries to tell Wal what to do. There's a big fierce cat called Horse who terrifies many of the other characters. There are a cow, a goat, geese, a ram called Cecil, a corgi dog called Prince Charles, a girl called Pongo, a boy called Rangi, and many other characters.

They are all very real to Murray Ball, and so are the places where they live. He knows just what Wal's back door looks like, and his living room, and the kennel where the dog lives, and so on.

But there's something wrong with that world when Murray Ball goes into it every morning. He can't just lean over the fence and enjoy watching it, because it's all standing still—nothing's happening. And nothing will happen until he thinks something up.

He lets his mind wander around the possibilities. Perhaps something could happen to Prince Charles, the corgi. Perhaps it could be lambing time at Footrot Flats, and something could happen to do with that. . . . He tries to look at each possibility from all sides to see if he can get anything out of it.

It's hard work, trying to pull ideas out of the air. He says that when he begins, "It's the same sort of feeling as if you've got a pile of fence battens to carry up a hill. You know they've got to go up the hill. You know, once they're up there, they're going to be of use. But it's still an effort to bend down, and pick them up, and carry them up that hill."

Suddenly, the beginning of an idea will come into his head—it might be some words which seem funny, or a funny little picture. It is almost like an electric shock in his brain. However small it seems, he knows it will be enough to work on.

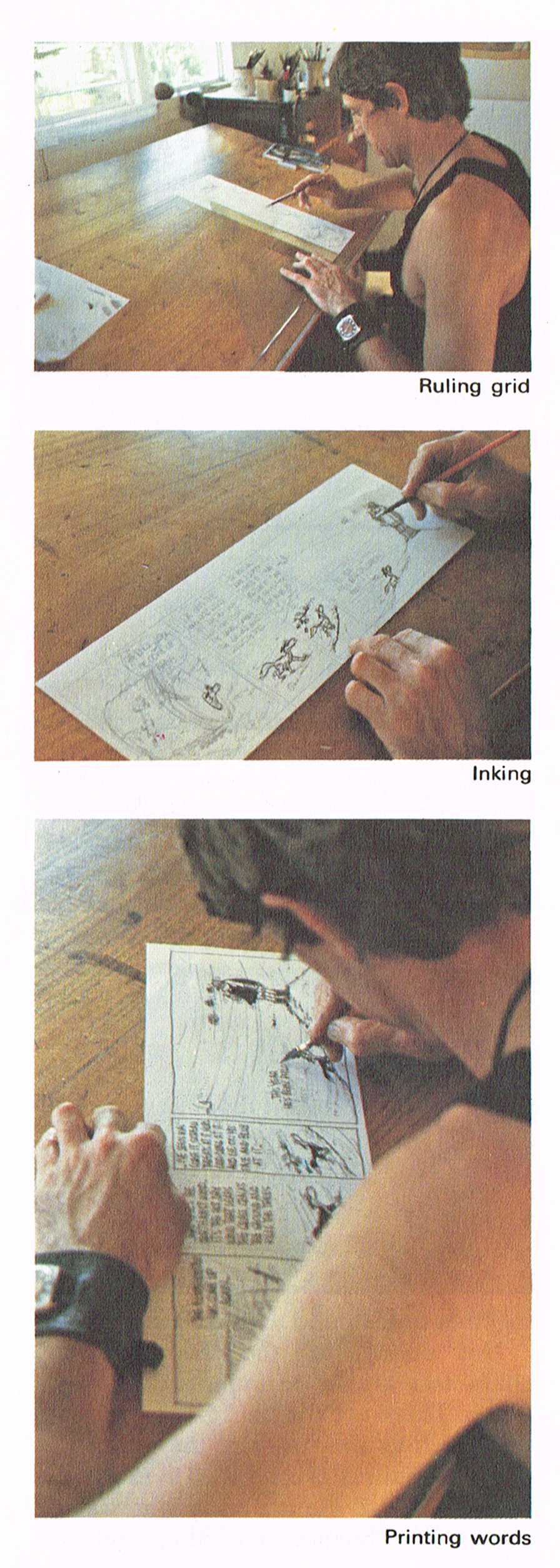

He keeps thinking about it, until he has worked out a whole episode, with a beginning, a middle and an end, and scribbles sketches in his notebook of what the characters will do and say.

Then he leaves that and tries to think of another idea.

Each day he tries to think of three ideas. He has to produce six Footrot Flat strips a week, every week of the year. He has to keep his notebook as full of ideas as he can, to allow for times when he will be sick, on holiday, or for some other reason unable to work.

He also has to allow for those ideas that may not be good enough to use. After he has jotted down an idea during one of his morning visits to Footrot Flats, he doesn't look at it again for about a month. If it doesn't seem funny enough when he looks at it then, he will have to scrap it.