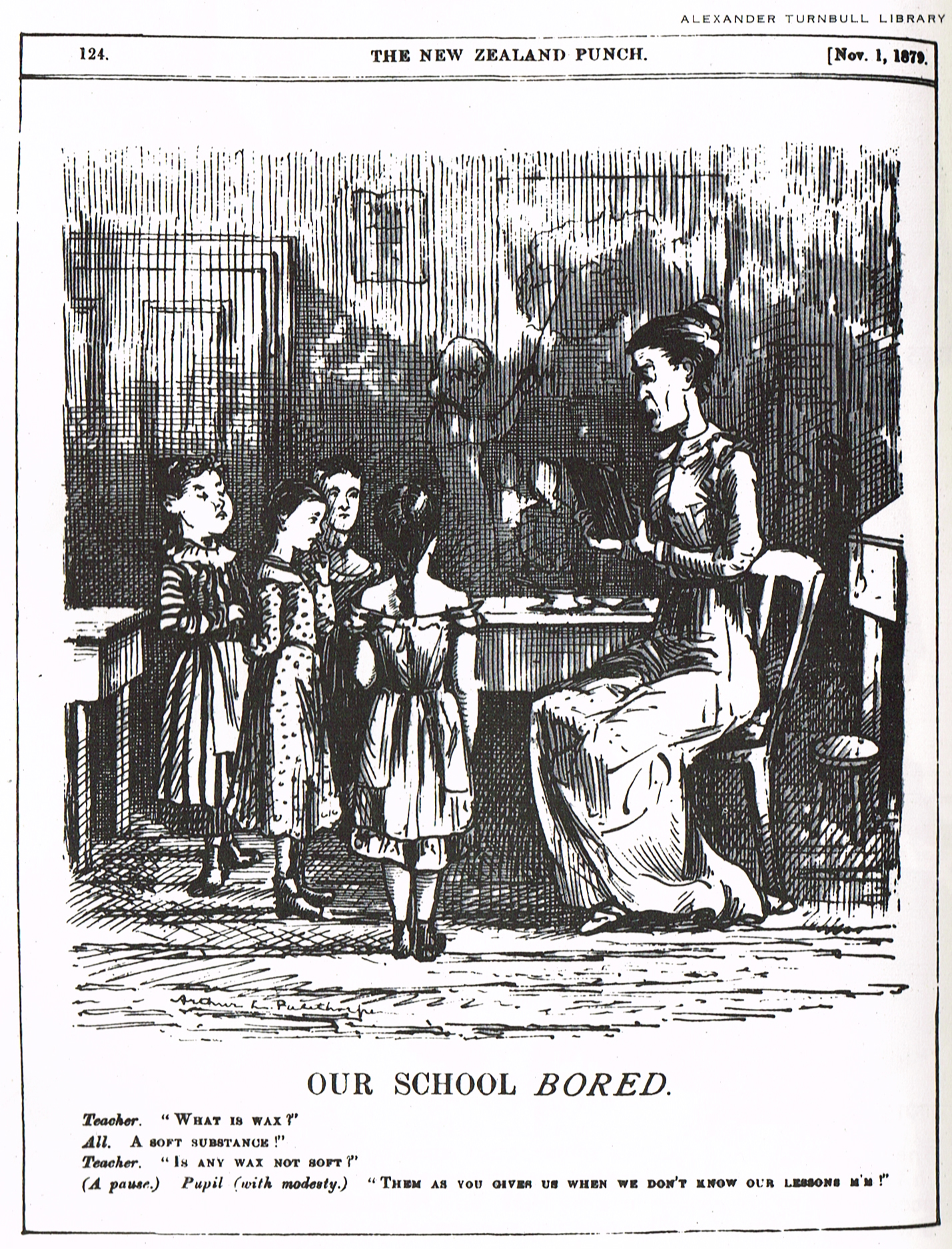

The several page article 'The Cartoonists' appeared in the weekly New Zealand Heritage magazine published in the early 1970's and eventually collected as a set of Encyclopedias.

Read The Cartoonists Part Three

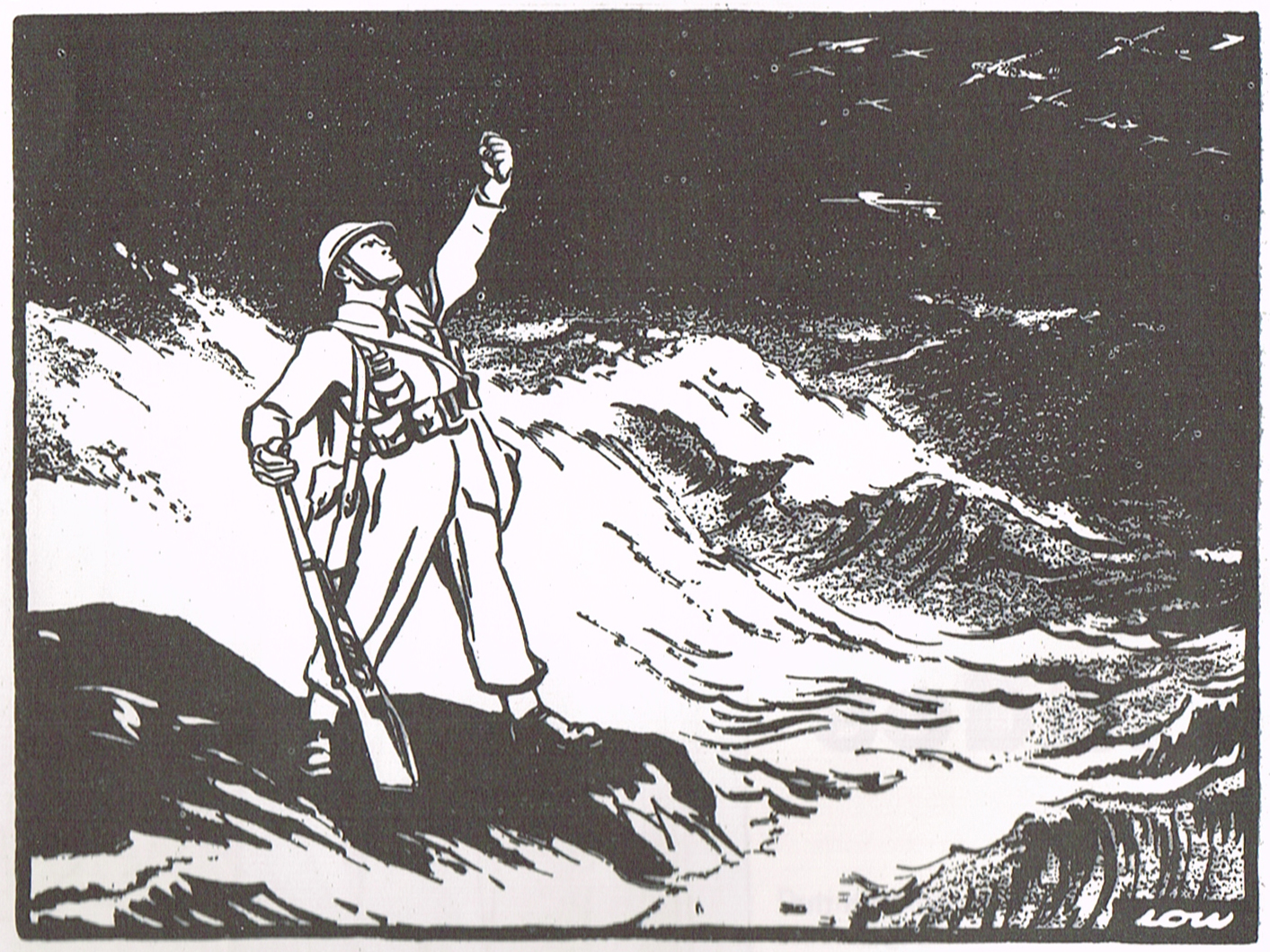

In the conservative newspapers for which they worked Minhinnick fitted naturally, whereas Low was a radical, an oddity who made his own rules. Minhinnick dryly pointed the political difference. "It is often written of a cartoonist that he 'crystallises and reflects the opinions of the common man'. If Low ever did that it was by coincidence. What Low crystallised and reflected were the opinions of David Low, and if the common man or anyone else didn't like it, they could do the other thing."

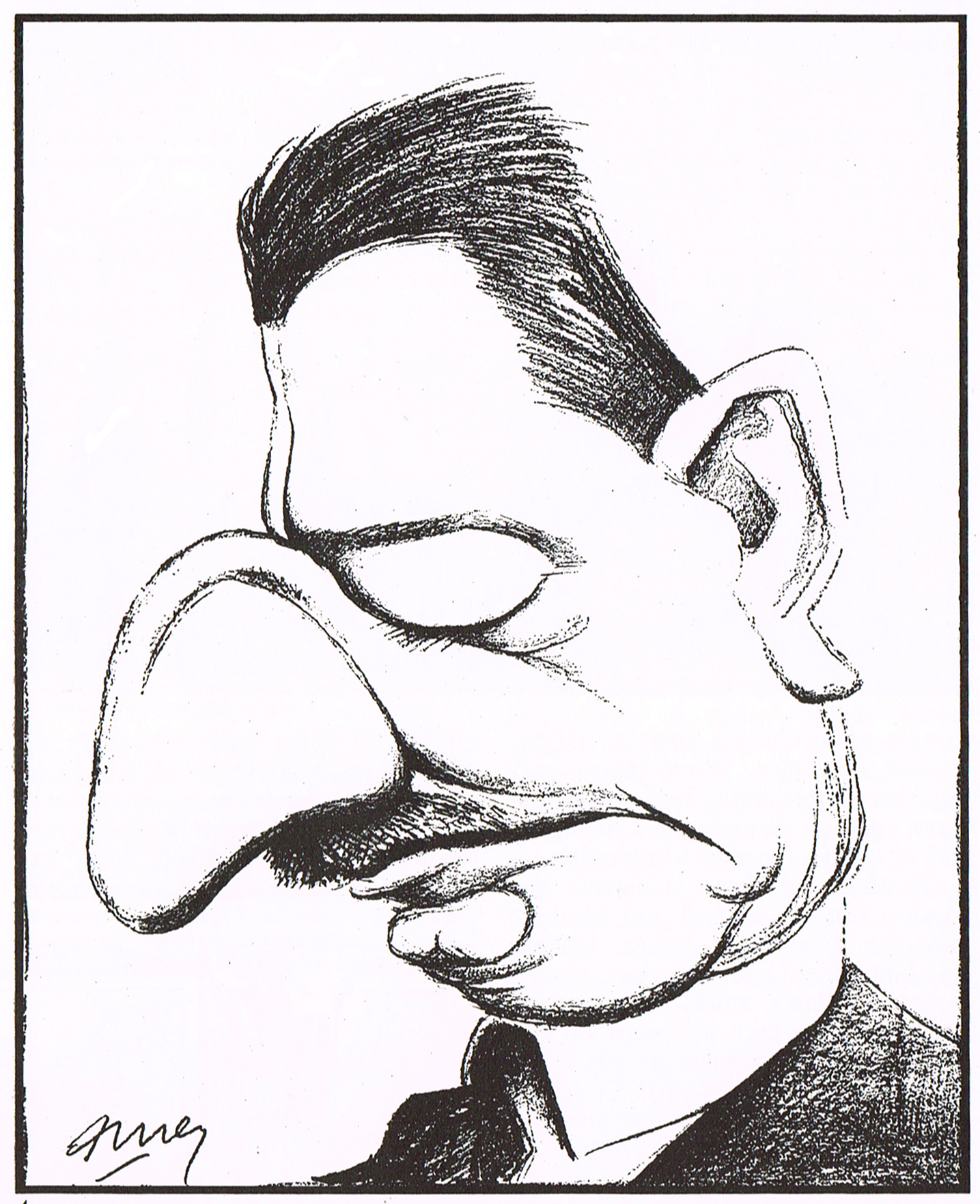

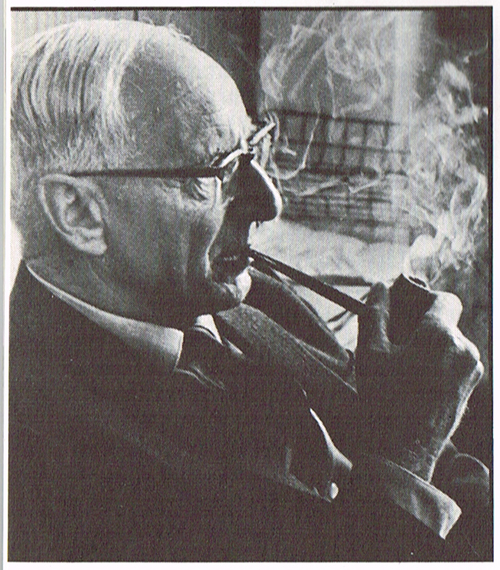

Gordon Minhinnick

Minhinnick considered Low's caricatures as being not merely recognisable but ludicrously unmistakable —the very essence of the person. Yet he discerned in Low the quintessential imp who would not have cared overmuch had he been wrong, and he quotes Low as saying that the first essential of caricature is that it should be a lark. Low would have liked that. He wrote in his own introduction to H. R. Westwood's Modern Caricatures: "Satirists who approve beauty and goodness by idealising the persons and policies of their friends do so, of course, at the expense of the satirical essence of their art, and become accordingly dull. Satire can-not live with hero worship, and poetry is no part of the caricaturist's function. However the ethics of satire may be tortured in argument, it is difficult to hold that the satirist has any moral obligation to his fellows but to throw bricks at them."

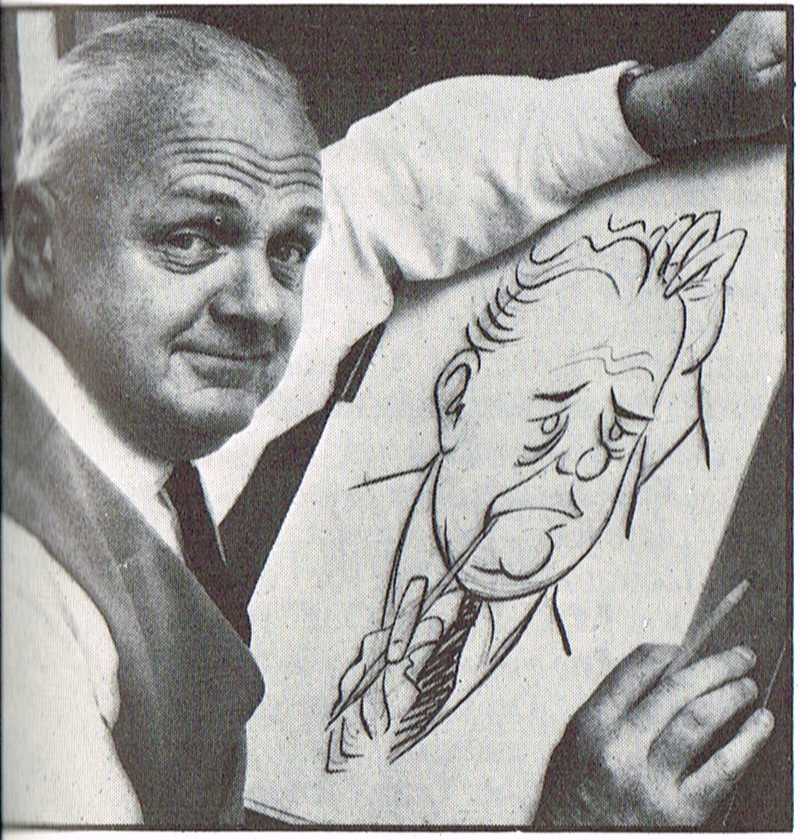

Nevile Lodge with self portrait at his drawing board

Where then are New Zealand's brick throwers? Minhinnick was one, though he seems to have mellowed with age. In the New Zealand Herald of July 15 1938 he depicted the Prime Minister, M. J. Savage, drinking a glass of State control, while Stalin, Mussolini and Hitler reach out for the bottle at his elbow. The caption is "The Spirit of his Ancestors". In that year, it is safe to assert, at least 60 per cent of Minhinnick's readers must have hated him for that.

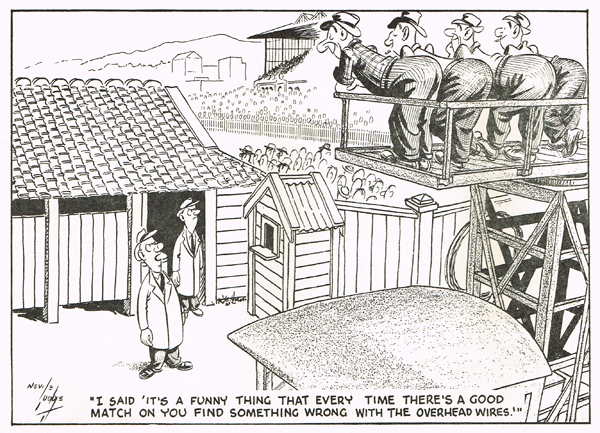

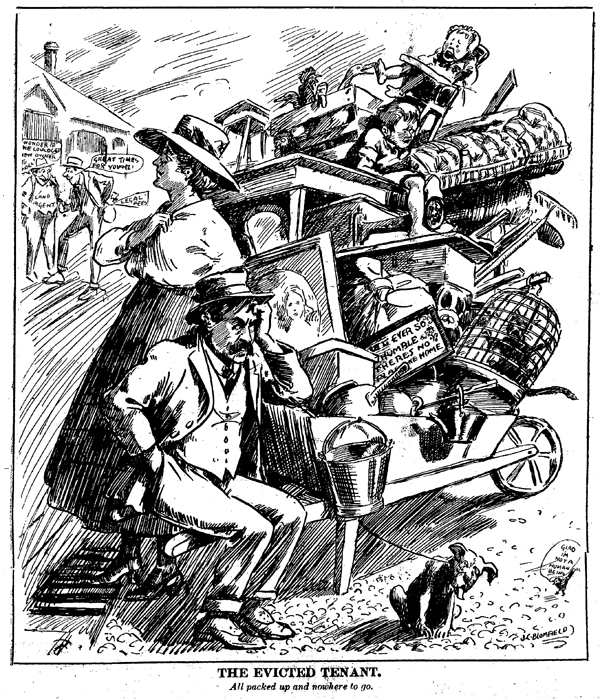

By April 15 1969 Minhinnick was drawing — for example — Sir Edmund Hillary in an "Attempt on the North Face of Mt. Muldoon", and his brick is thrown accurately but with markedly less force. Nothing like George Finey's wicked caricature of Gordon Coates has lately been seen. It is as though New Zealand's cartoonists in the end are moulded by their audience—a people who expect cartoons to be funny rather than biting, who set limits well within those imposed by libel laws.

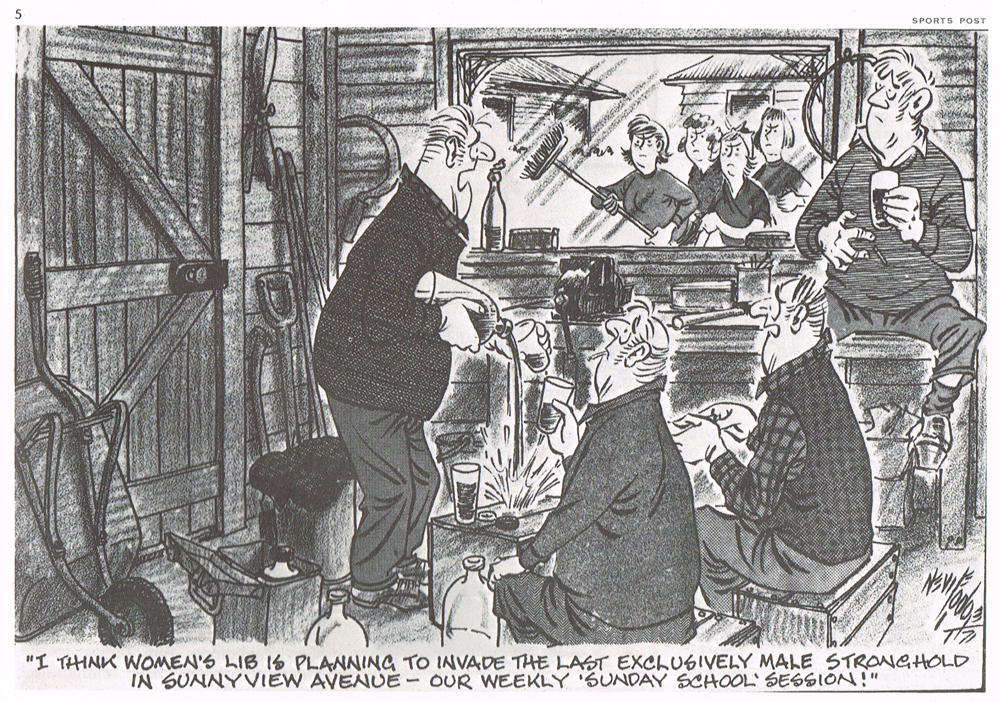

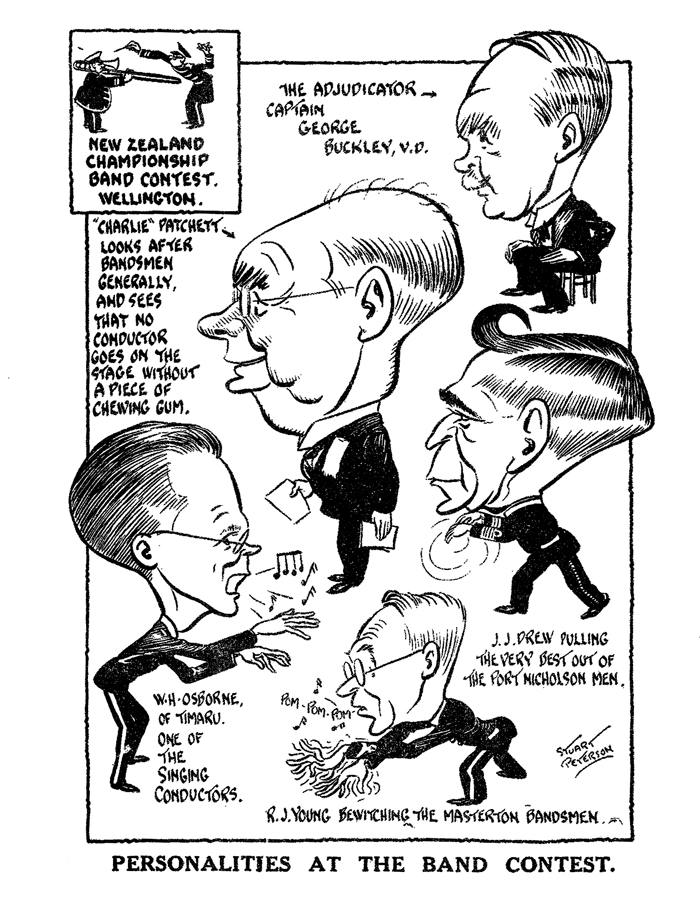

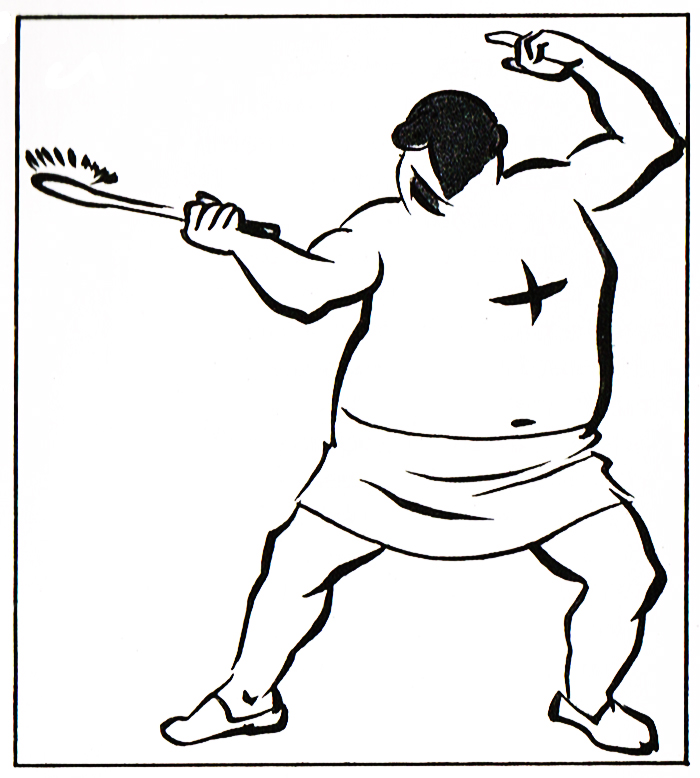

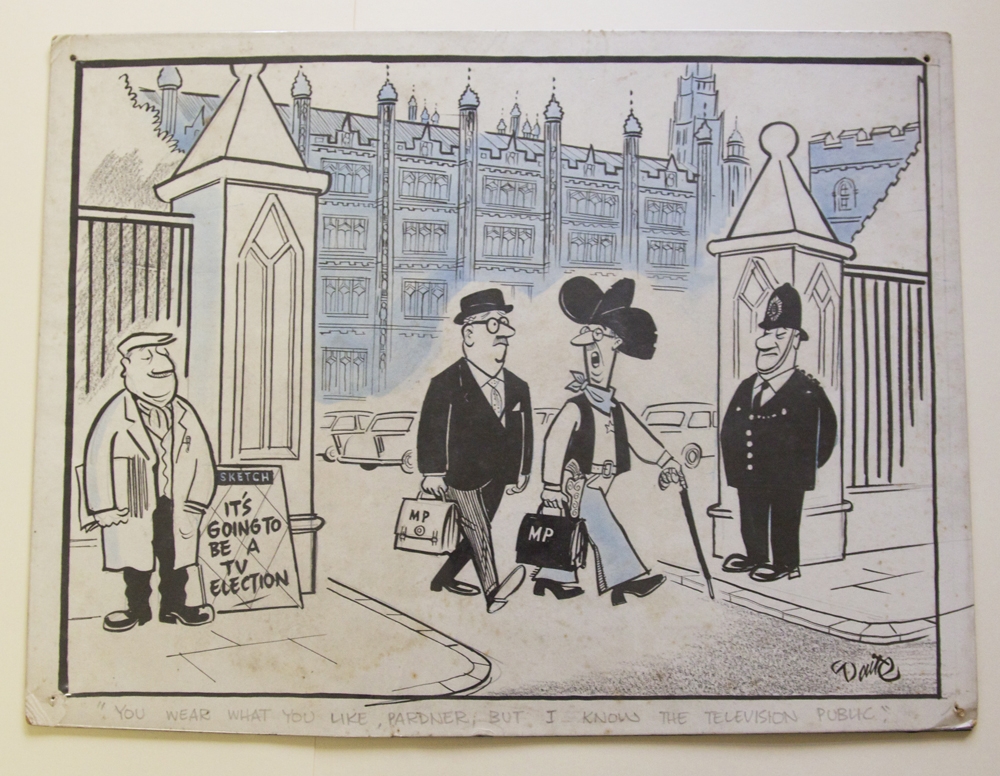

This 1971 Lodge cartoon is typical of the "average" New Zealanders he is most at ease in depicting, those whose primary interests are rugby, racing and beer.

Nevile Lodge (Evening Post) and Eric Heath (Dominion) consider that newspaper readers have become more rather than less sensitive since the flowering of New Zealand cartooning in the 1920s. "I am amazed at how outspoken those men were," Nevile Lodge has said. "We could not get away with it today. Their barbs seemed to be aimed at the character rather than at his ideas or policies."