The several page article 'The Cartoonists' appeared in the weekly New Zealand Heritage magazine published in the early 1970's and eventually collected as a set of Encyclopedias.

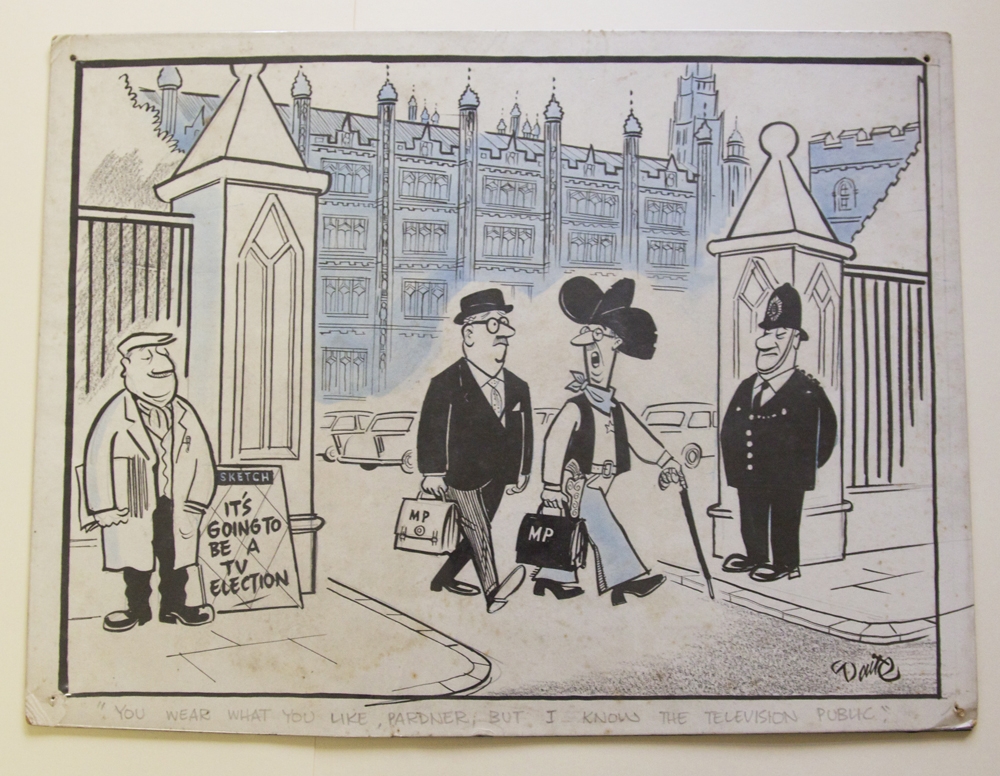

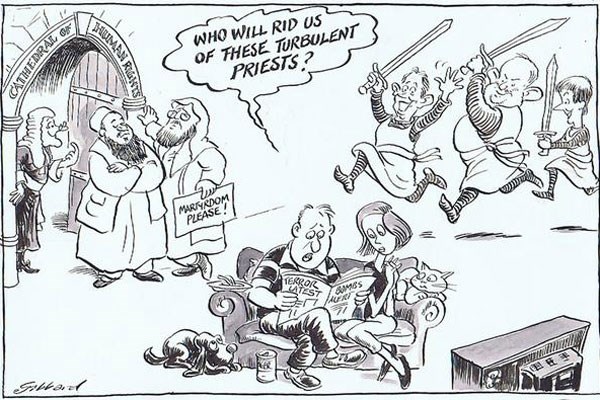

Les Gibbard

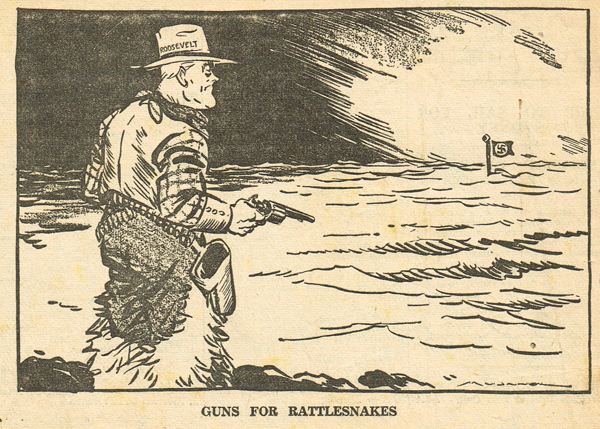

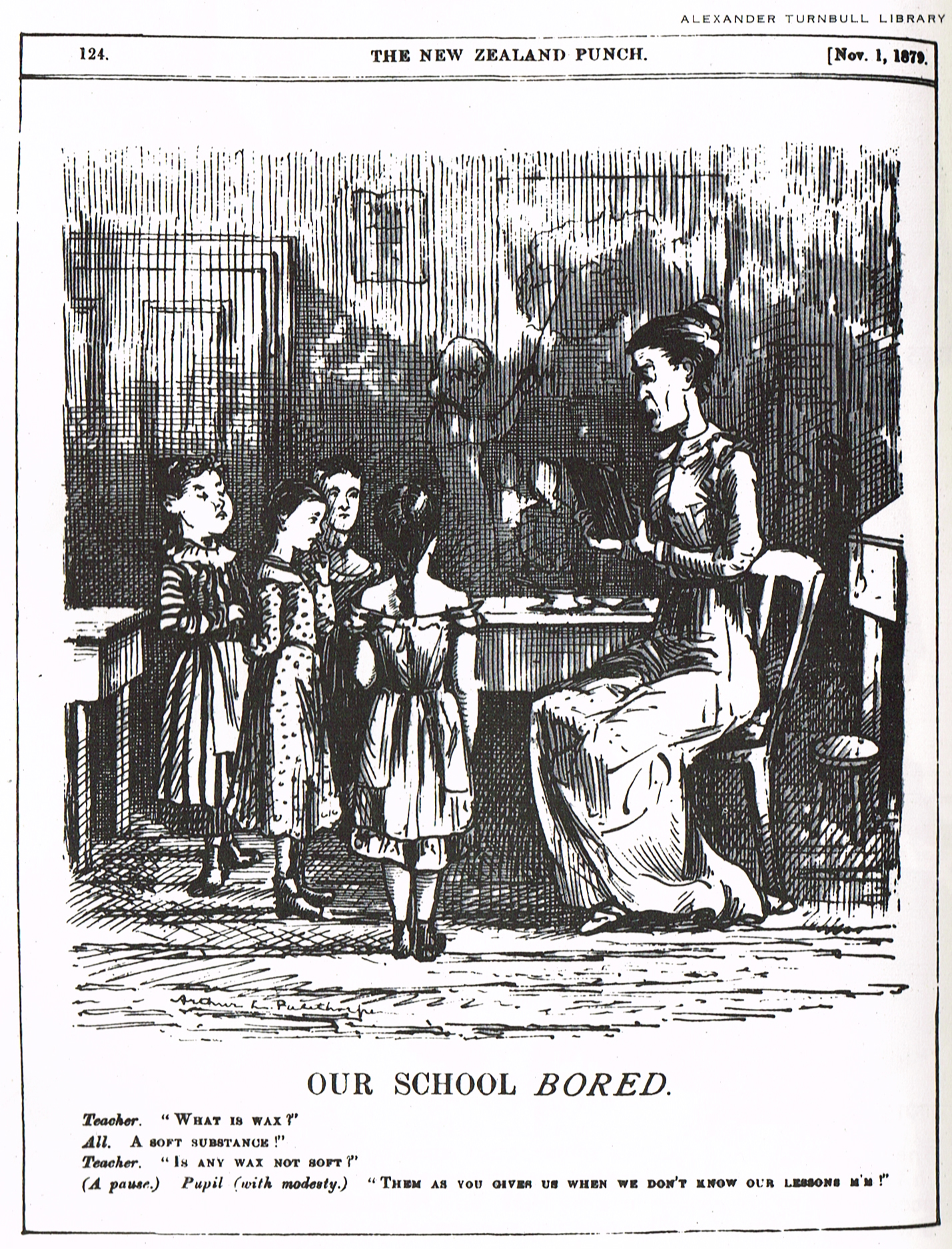

The easy, deceptively casual style of Les Gibbard's cartoons with their minimal captions seems to place much more than a century between him and the skilled academic artist Arthur Palethorpe, whose drawings in the New Zealand Punch, of Wellington, are among the first which can properly be called cartoons. Even in "colonial" clothing, Palethorpe's figures were formal and wooden, and some unconscionably long captions were needed to put across his jokes.

Palethorpe's wit is of interest, though, in that as long ago as 1879 it took a favoured New Zealand form—the pun.

"If I go spinning yarns among silks and satins I am sure to be worsted." Teacher: "What is wax?"

All: "A soft substance."

Teacher: "Is any wax not soft?"

Pupil (with modesty) : "Them as you gives us when we don't know our lessons M'm."

A wince to every page. Yet 70 years later the pun was still humouring New Zealanders. In the Otago Daily Times of August 20 1951, Keith Waite marked the wreck of the former inter-island ferry Wahine near Timor as she transported troops bound for Korea: a soldier leaning over the rail of the grounded ship says to another—"Yer can't really blame her—she's used ter running inter-islands!"

David Low (1891 - 1963), from a photograph by Karsh of Ottawa. Low was knighted the year before his death.

With few exceptions the cartoonists of the late 19th century were anonymous. Their work was inferior to Palethorpe's—which is to say, very inferior—except for J. H. Wallis (c. 1880) who could caricature a face but was inexcusably careless about the rest of the drawing. Although some of them tried to distinguish their characters as New Zealanders pictorially, they failed to do so in their captions. These showed all too clearly the Englishness of the journal from which they were pirated.

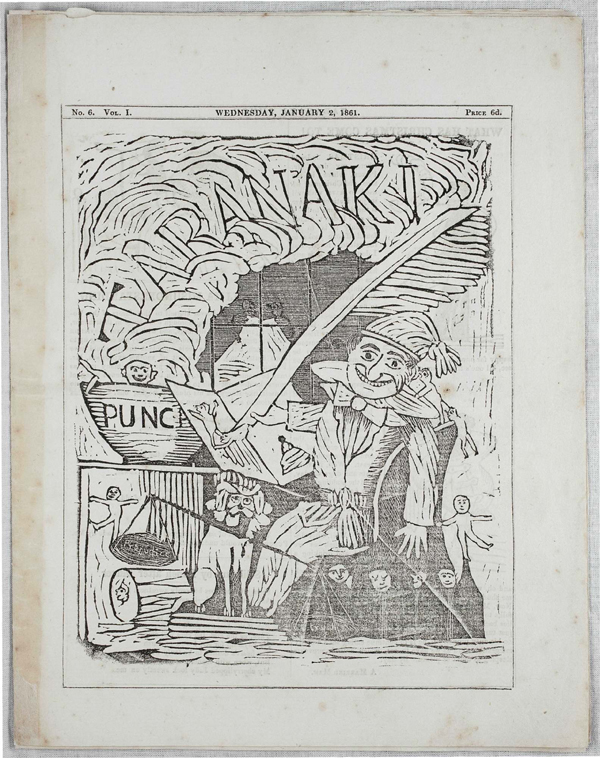

Woodcut cartoons from the Taranaki Punch - ARC2002-538 Taranaki Punch, Collection of Puke Ariki, New Plymouth, New Zealand.

The daily-paper cartoon had not then arrived, and cartoon humour appeared only in periodicals patterned on Punch and usually bearing its name. The New Zealand Punch was markedly the best of four which appeared for varying periods—usually short—in the four main cities. The Auckland Punch, for example, was abysmal, though one of its rough unsigned cartoons in the issue of August 19, 1865 shows that New Zealand egalitarianism is not a recent phenomenon.

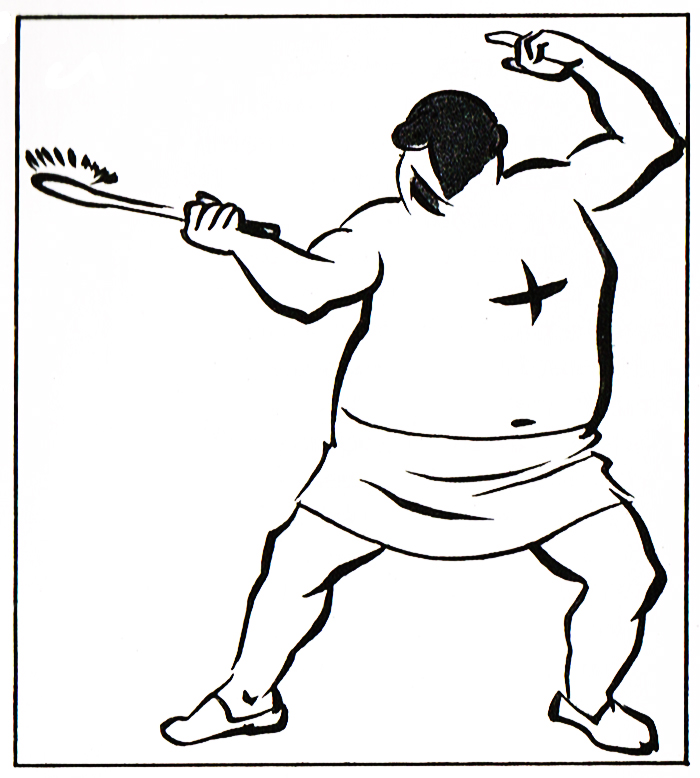

Foreigners often remark on that attitude, with cause. New Zealanders have built a welfare state and a largely classless social order on the premise that Jack is as good as his master. In so doing they have robbed the cartoonist of some handy stereotypes. Low's trade-union draught-horse would be possible in New Zealand; never his Colonel Blimp.

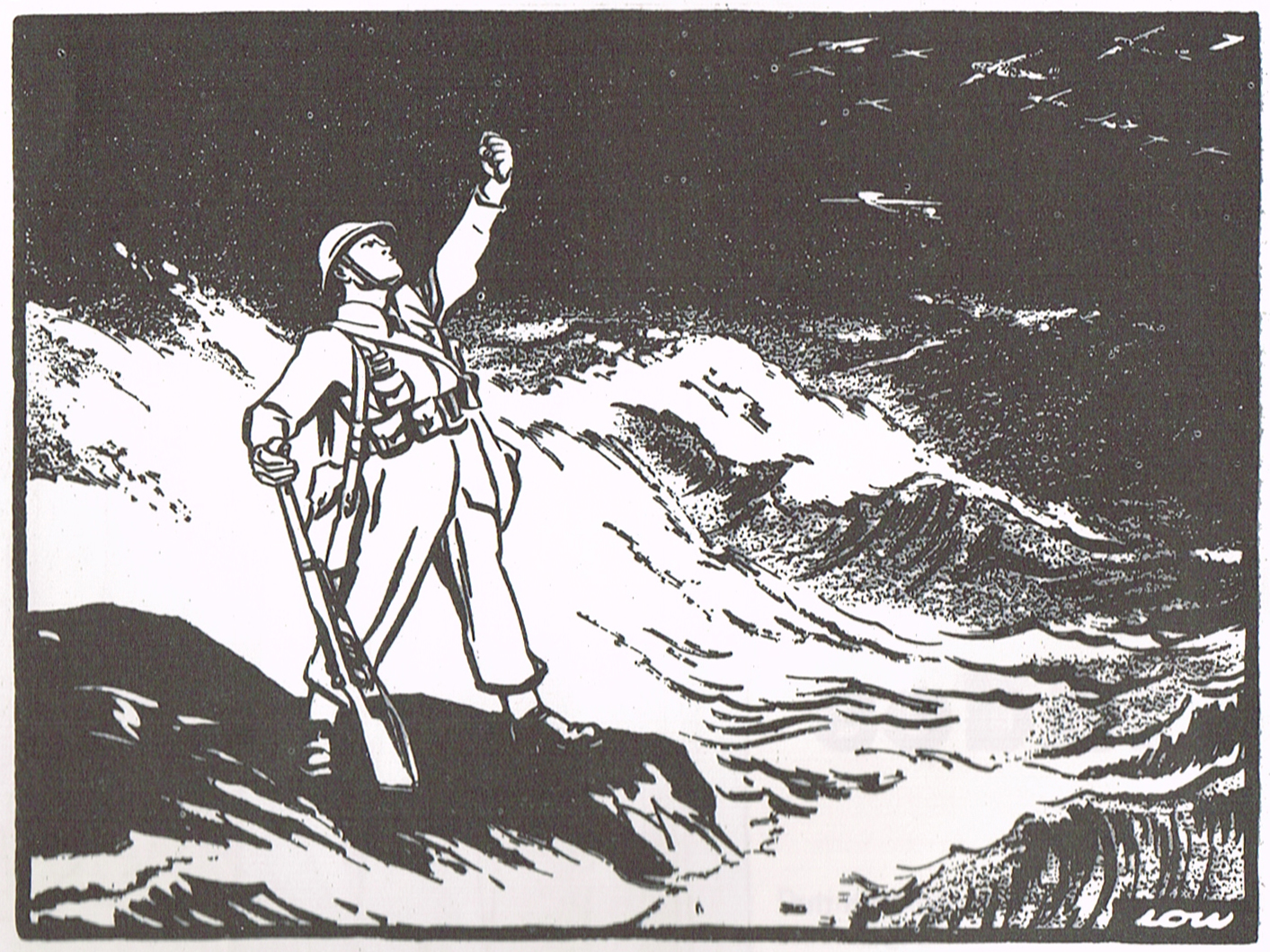

"Very Well, Alone", probably Low's most famous cartoon, was published at the beginning of the Battle of Britain in 1940.

New Zealand's cartoonists have not wasted tears on the difficulty. They simply cultivated (in earlier years) the personal and individual art of caricature, and searched always for a Mister Average, a Common Kiwi, who would be the prototype of the overtaxed, downtrodden, put-upon, unassertive, wife-ridden ordinary man.

A. S. Paterson cartoon featuring Little Eric of Berhampore.

Sir Gordon Minhinnick's John Citizen

In Minhinnick's work this character appears as John Citizen, a mild fellow commonly seen as a bemused observer of events contrived by politicians and others for his discomfort. In A. S. Paterson he is Little Eric of Berhampore. In John McNamara he is a young Maori (occasionally labelled "NZ") at times sitting on the sidelines, at other times engaged in some activity related to the main theme but taking the form of a sub-cartoon. In Sid Scales he appears as a "typical" long-nosed, genial, carelessly groomed male who could reasonably be labelled Joe Blow.

Nevile Lodge, the Evening Post cartoonist, focuses similarly on a "middle" New Zealand couple, yet claims to have sought consciously for a "class" character to give edge to his work. "In drawing the domestic situation," he has said, "I use a middle-class sort of person—not because it's the way we all are, but because you get more pomposity among those living on the fringes of the filthy rich. I think it's better to make fun of somebody who thinks he's a little better than the average."

"Colonel Blimp", the figure invented by Low in the 1930's to satirise the British Establishment.