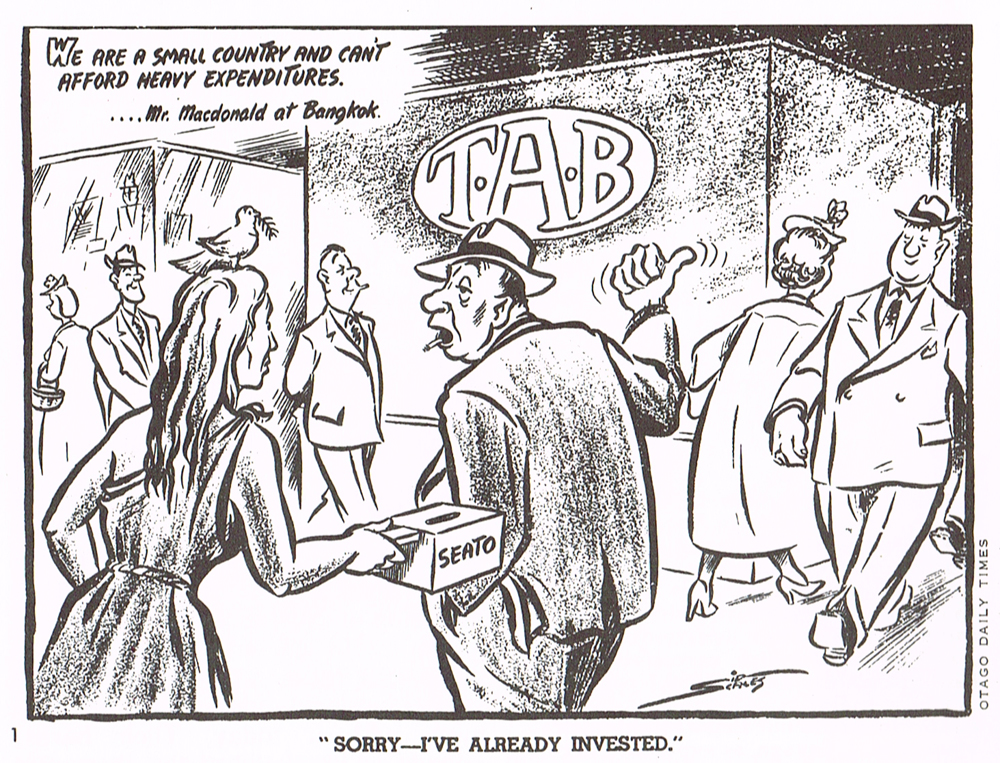

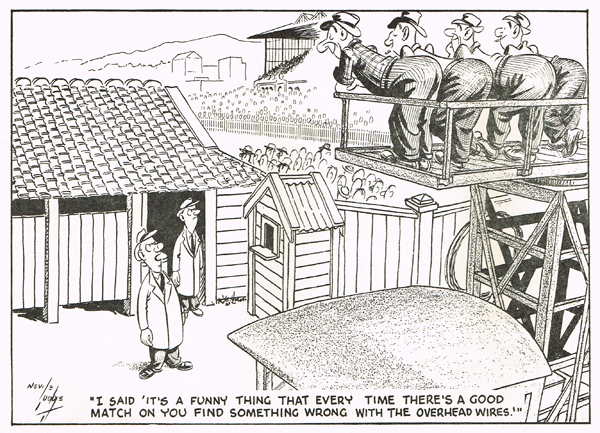

In this 1955 commentary on New Zealand's meagre contribution towards the South East Asia Treaty Organisation, Sid Scales of the Otago Daily Times shows less indulgence than Nevile Lodge towards New Zealanders' preoccupation with horse racing. The quotation is from T. L. Macdonald, Minister for External Affairs 1954-57.

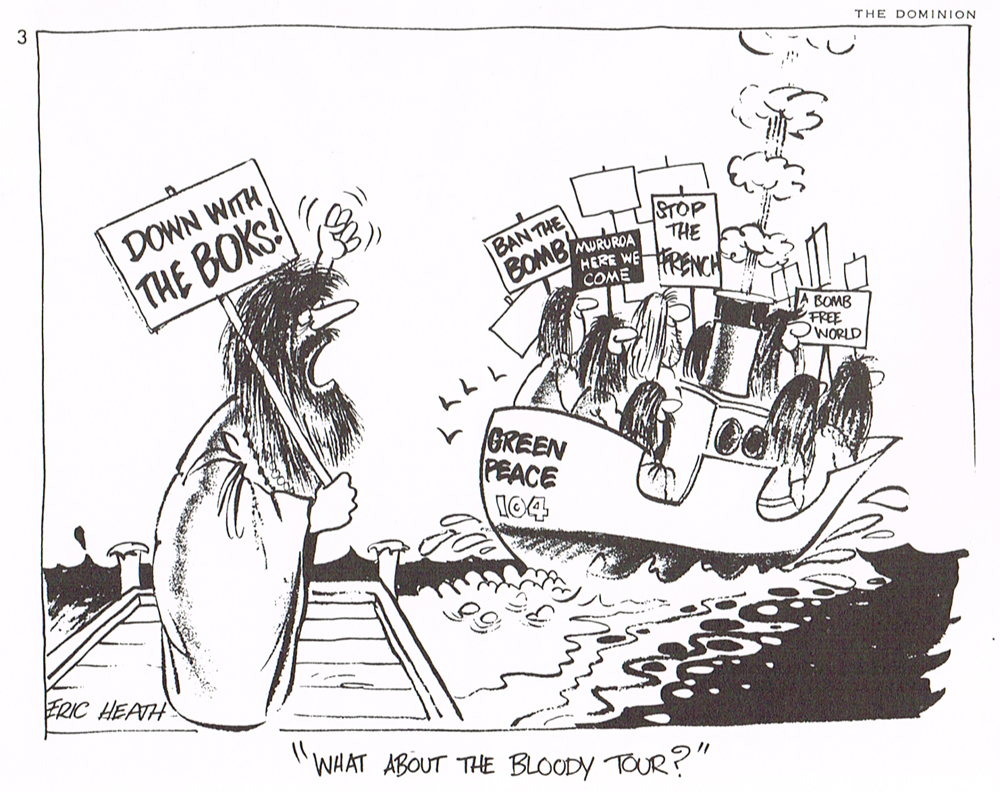

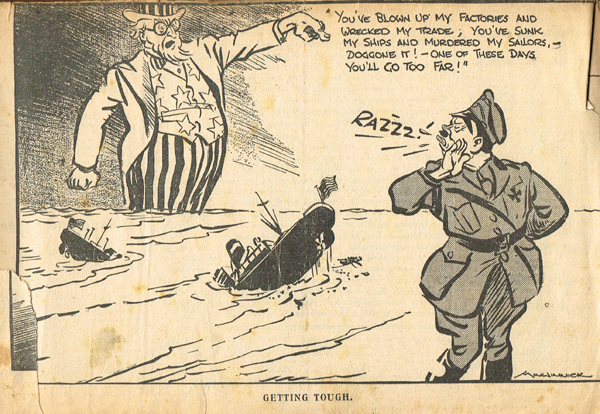

Eric Heath, an admirer of the vitriolic Petty of The Australian, has asserted that New Zealanders live under a lot of umbrellas. "Anything I do that stabs people at all brings a flood of protesting letters. Readers are very sensitive, and there is a reluctance to draw such figures as the Queen or the Pope, which cartoonists in any other country can draw."

New Zealanders in the 1970s seem happier with the Giles type of man-in-the-street humorous cartoon than with hard political satire. It accords with a national character which Heath has defined as peace-loving, good-humoured, easy-going and domestic. Lodge agrees with that assessment, adding to it only an unreadiness to change unless overwhelming reasons are offered.

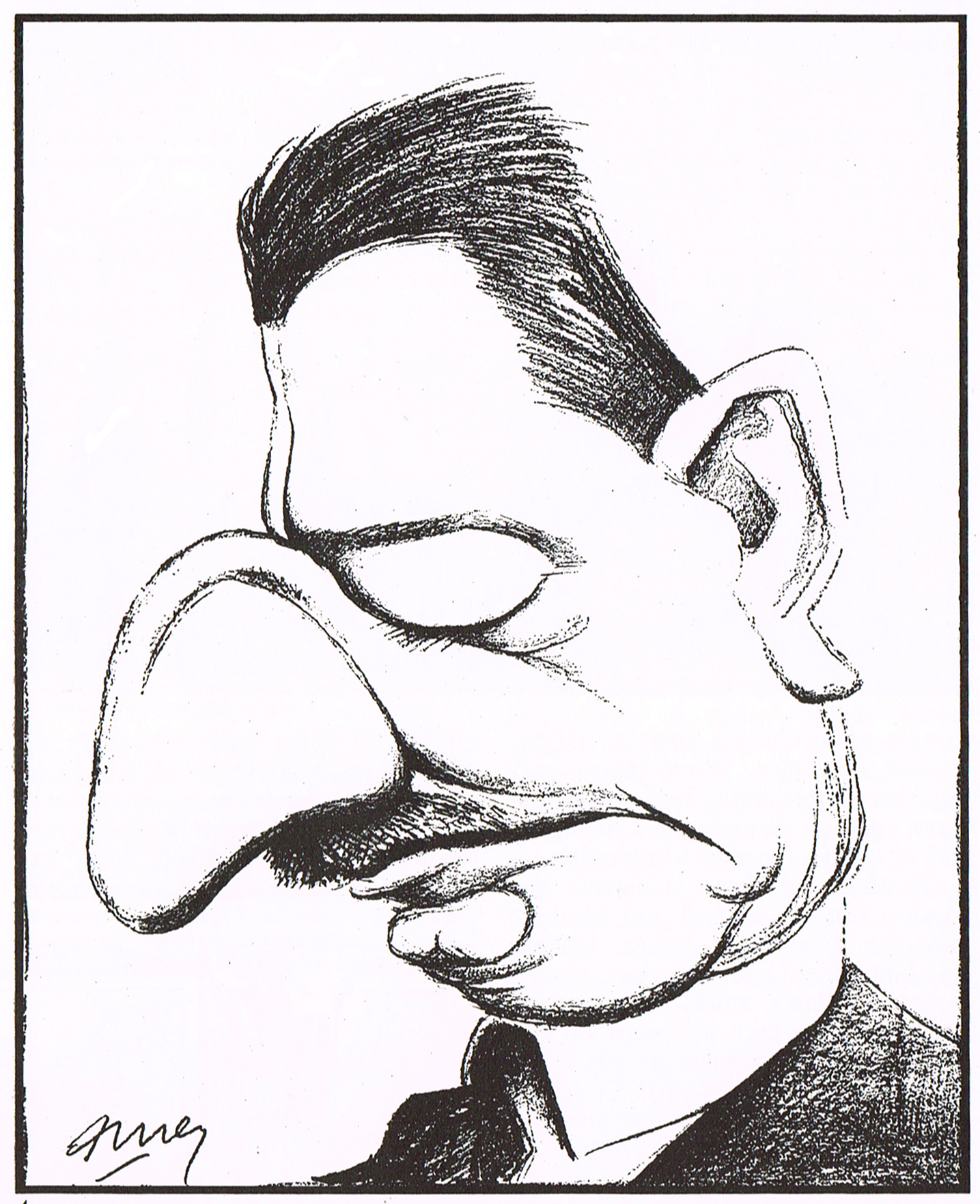

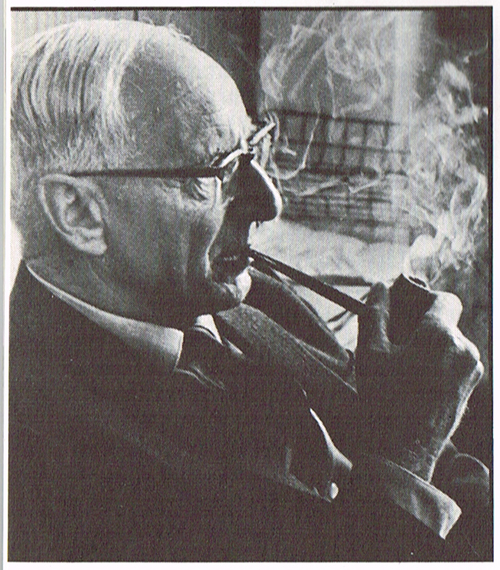

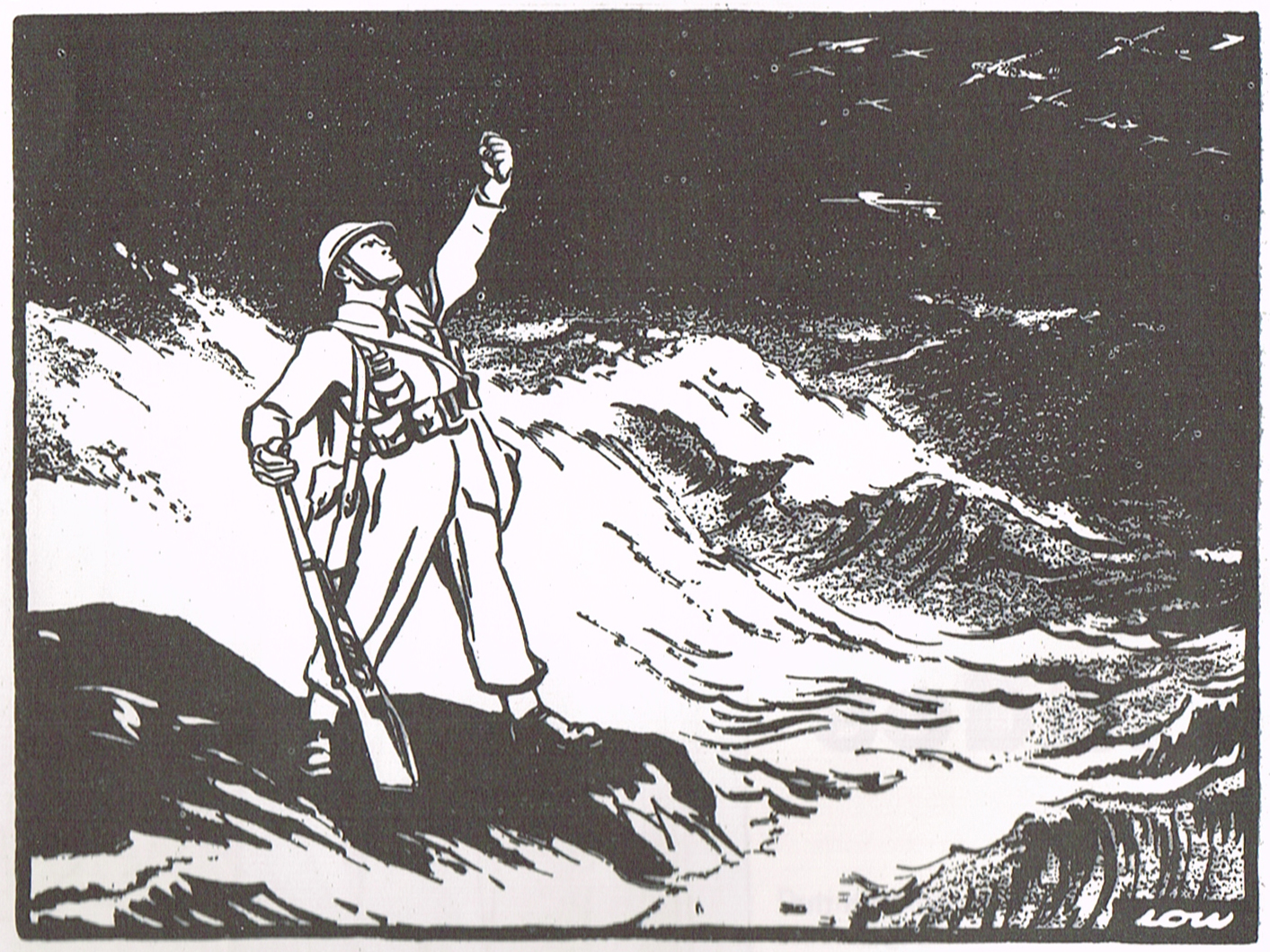

In this conservative, neighbourly milieu, caricature pure and simple has vanished and its use in cartoons has declined. Nor does New Zealand welcome extreme scepticism of the kind exhibited by Low in the year of his death, 1963. In such cartoons as "Man the Lord of Creation" Low seemed to be summing up a lifetime of close observation of his fellow men. The thrust was verbal rather than pictorial—but devastating. His Ten Commandments, for example, are "Don't Get Found Out" repeated 10 times. On his wall also is a house-hold motto: "Do Others Before They Do You.", A nation which expects cartoonists to be funny men might well have disowned one of its greatest sons—if it had seen his work.

Certainly cartoonists of nearly equal calibre working in New Zealand have eschewed satire in favour of a gentler, more humorous social commentary. They have performed superbly, as might be expected of men stooping slightly from higher purposes.