Murray Ball

by Jane Thompsen, originally appeared in School Journal, 1984, Part 4, number 2.

AT NINE O'CLOCK every morning, from Monday to Thursday, Murray Ball goes to a quiet place to think of ideas for his cartoons.

He might go to the top of a hill near his house, or under a tree in the garden. It has to be somewhere he won't be disturbed—because he needs to sit down, make himself comfortable, and go into a kind of a dream. It is almost like going through a door, shutting it behind him and finding himself in another world—the topsy-turvy world of Footrot Flats.

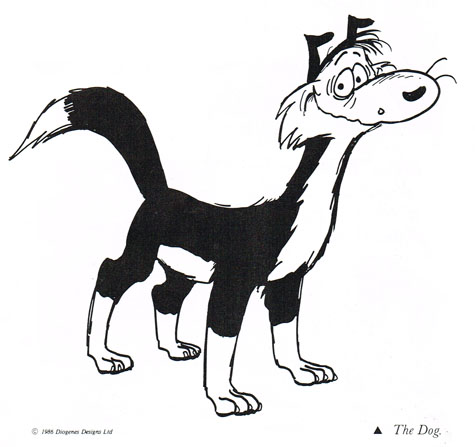

Many characters whom he knows very well live in that world. There's Wal, a farmer, thoughtless and dour and mean, who also has some good qualities—he would never do anything dishonest. There's his dog, who adores him and would do anything for him, although he tends to be rather greedy and jealous. There's Gooch, a much more sensitive farmer, who even tries to protect pests such as blackberry and possums. There's fussy Aunt Dolly, who tries to tell Wal what to do. There's a big fierce cat called Horse who terrifies many of the other characters. There are a cow, a goat, geese, a ram called Cecil, a corgi dog called Prince Charles, a girl called Pongo, a boy called Rangi, and many other characters.

They are all very real to Murray Ball, and so are the places where they live. He knows just what Wal's back door looks like, and his living room, and the kennel where the dog lives, and so on.

But there's something wrong with that world when Murray Ball goes into it every morning. He can't just lean over the fence and enjoy watching it, because it's all standing still—nothing's happening. And nothing will happen until he thinks something up.

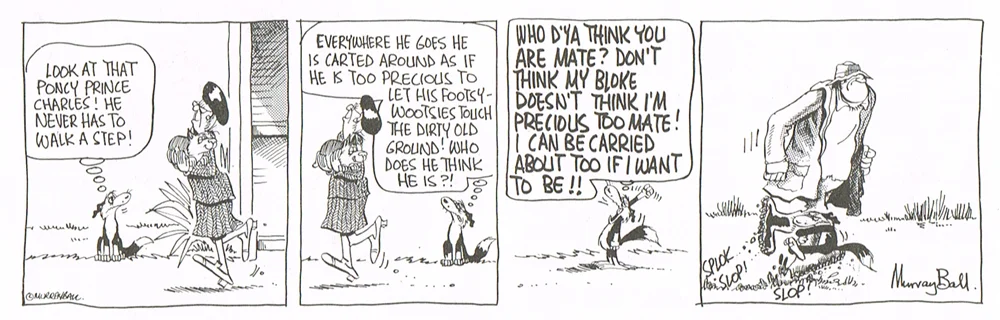

He lets his mind wander around the possibilities. Perhaps something could happen to Prince Charles, the corgi. Perhaps it could be lambing time at Footrot Flats, and something could happen to do with that. . . . He tries to look at each possibility from all sides to see if he can get anything out of it.

It's hard work, trying to pull ideas out of the air. He says that when he begins, "It's the same sort of feeling as if you've got a pile of fence battens to carry up a hill. You know they've got to go up the hill. You know, once they're up there, they're going to be of use. But it's still an effort to bend down, and pick them up, and carry them up that hill."

Suddenly, the beginning of an idea will come into his head—it might be some words which seem funny, or a funny little picture. It is almost like an electric shock in his brain. However small it seems, he knows it will be enough to work on.

He keeps thinking about it, until he has worked out a whole episode, with a beginning, a middle and an end, and scribbles sketches in his notebook of what the characters will do and say.

Then he leaves that and tries to think of another idea.

Each day he tries to think of three ideas. He has to produce six Footrot Flat strips a week, every week of the year. He has to keep his notebook as full of ideas as he can, to allow for times when he will be sick, on holiday, or for some other reason unable to work.

He also has to allow for those ideas that may not be good enough to use. After he has jotted down an idea during one of his morning visits to Footrot Flats, he doesn't look at it again for about a month. If it doesn't seem funny enough when he looks at it then, he will have to scrap it.

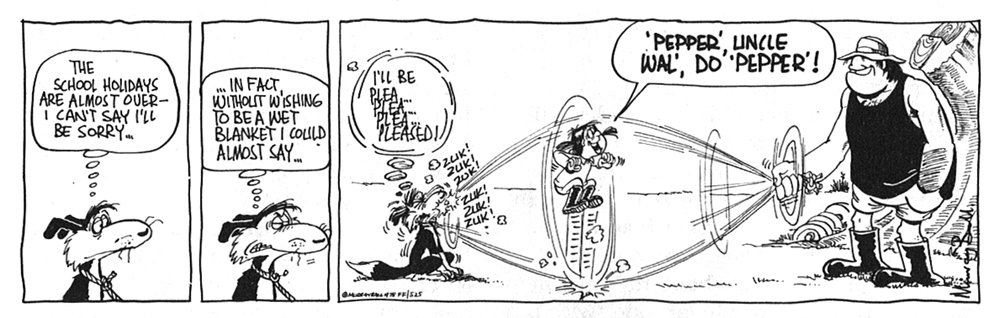

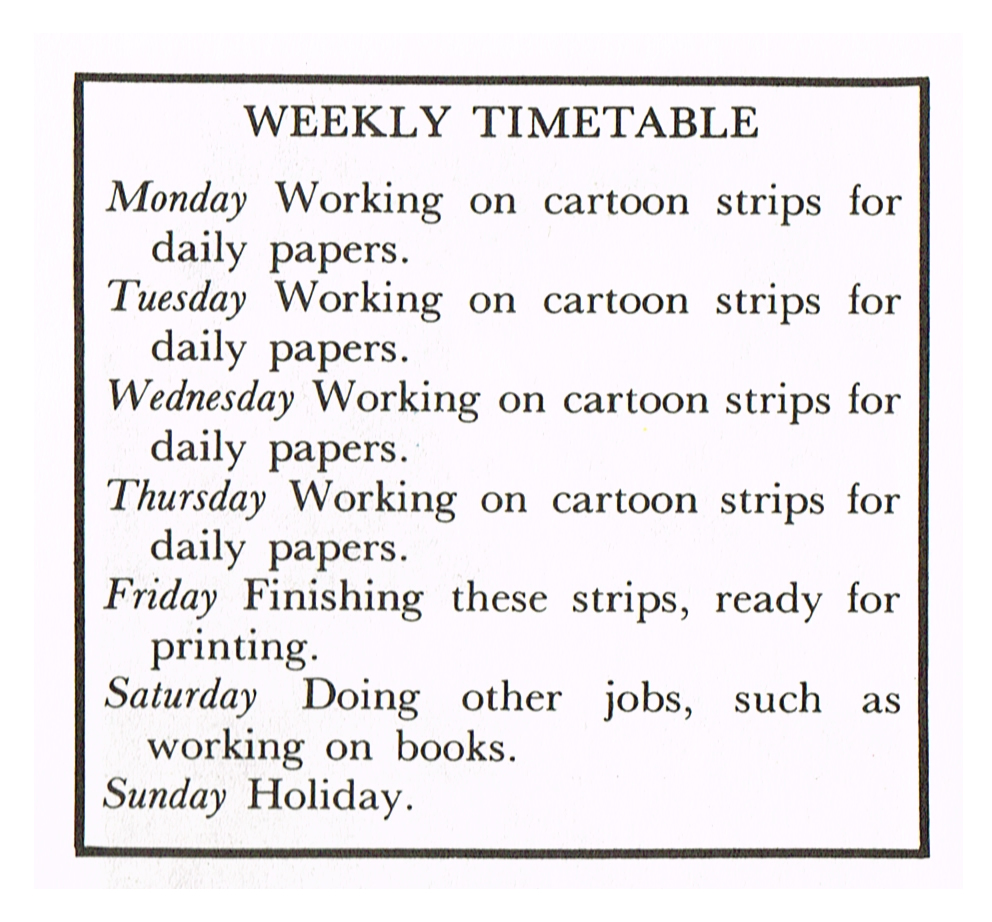

The beginning of the idea for this cartoon was a funny little picture which popped into Murray Ball's head—the dog being carried around on Wal's feet. It arose from a memory of being carried round on his father's feet when he was a boy. Then he had to work out why Wal would be carrying the dog around like this.

This cartoon began with Murray Ball remembering a fence which hung down over the bank on his cousin's farm. He always wondered what it would be like to climb it.

Murray Ball's small daughter was once thumped on the head when she was holding a skipping rope. The memory of what happened came back into Murray's mind during an ideas time, and he imagined the same thing happening to the dog.

Murray Ball learned this trick of attracting birds when he was at teachers' college. He wondered what would happen in Footrot Flats if a lot of birds were attracted in this way, and at once he thought of Horse.

The joke about the way the dog hates his name began accidentally. Murray hadn't decided on a name for the dog when the very first Footrot Flats strips were printed. By the time twelve strips had been printed he had decided on the name, but then it seemed rather hard to work it in casually. In the end he decided to keep the name a secret, and only he and Pam, his wife, know it. Now he quite often has jokes about the dog's secret name in his cartoons.

In the Workroom

Murray Ball's ideas time is the most important and creative part of his work. But the ideas time is fitted into a busy working day.

Every morning, Murray gets up at 4.30 and goes out to the shed where he works. He works best early in the day.

He gets out his ideas book, and turns to the oldest idea in it. He makes sure that he still thinks it's funny—about once every two or three weeks he has to scrap one. Then he begins turning that rough idea into a cartoon strip ready to be printed in the newspaper.

He takes a sheet of paper which has been specially cut to the right size by a local printer—twelve by forty-two centimetres.

Then he begins working out where the frames should be. This is a very important part of making a cartoon, and there are several things to think about.

Most of the action has to be going from left to right, because that's the way we read. The figures in each frame have to be placed so that they don't seem to be bumping into each other. There has to be enough room to show a little background, without cluttering the picture. Above all, there has to be enough room for the most important scene. Murray might have to sketch this out first to see how much room it will take. Then he will fit the other scenes into the space that's left.

When he has worked out roughly the size and content of each frame, he can begin filling in the details of the pictures.

He is very practised in drawing all the characters. They have basic shapes which he always uses. He also knows roughly how to get the expressions he wants: for happiness, the eyebrows are raised, and the corners of the mouth are up; for anger, the eyebrows tilt towards the nose, and the corners of the mouth turn down; for sadness, the corners of the mouth still turn down, but the eyebrows are tilted up in the middle.

Of course, to get the exact expressions he needs for a particular cartoon, he may have to try over and over again, and he won't know just where he should put a little extra dot or line until he has done it.

As he is drawing, Murray doesn't feel that he is in the world of Footrot Flats. He is in the real world, practising his craft. There is quite a lot of tension in trying to get the drawings right. But he doesn't need the absolute concentration that he needs when he's getting ideas. He thinks drawing the cartoons must be a bit like a potter making a pot. His brain doesn't have to be giving his hands orders all the time—his hands seem to know what they're doing.

While he is drawing, he listens to the radio—especially news programmes and interviews. Early in the morning, he likes to get shortwave programmes—the B.B.C., Radio Moscow, the Voice of America, Radio Vietnam.

After about three-quarters of an hour, he has finished pencilling in the drawings. They look quite rough. But he knows now just how he wants the finished cartoon to look.

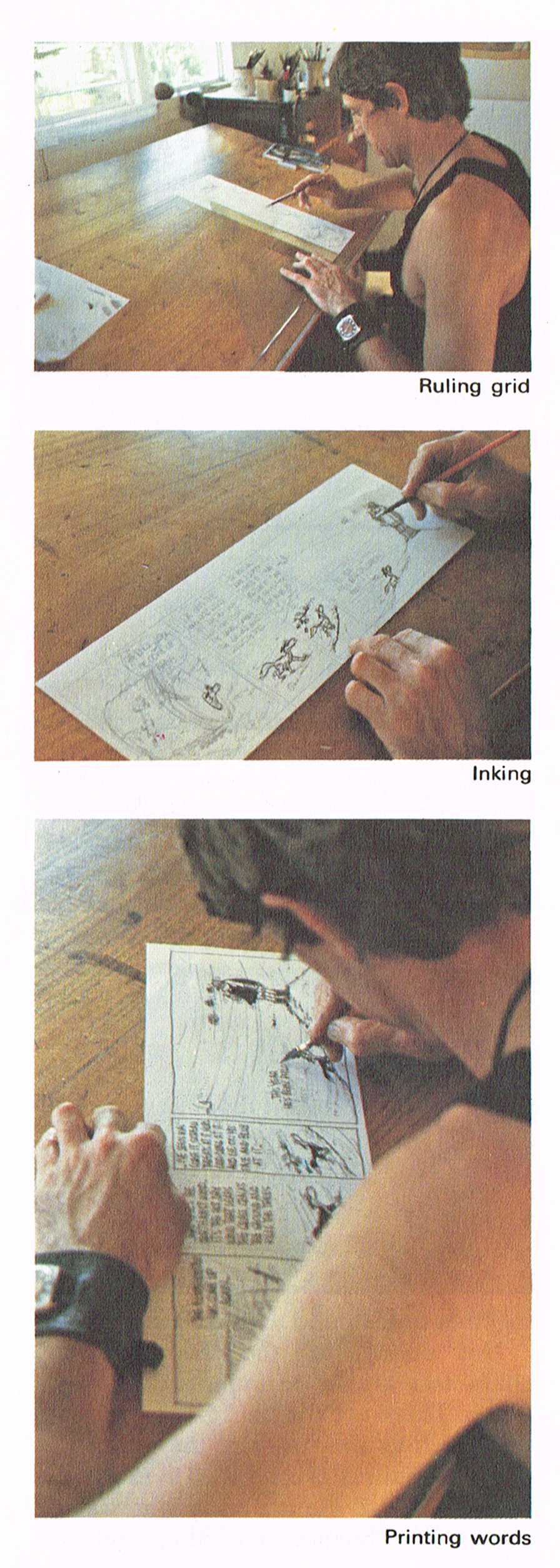

He rules a grid of lines over the cartoon, so everything will be straight, especially the lines of words.

Then he begins inking the cartoon in. In a way this is easier than the pencilling, because he knows just what he is doing. But in another way it is more difficult, because he doesn't want to make a mistake; this would be hard to alter so that it didn't show up on the finished cartoon. Luckily he hardly ever makes a mistake. The cartoon is almost always finished on the same piece of paper on which he began working out the frames.

The expressions on the characters' faces are the most important part of the cartoon, so Murray inks them in first with a fine nibbed pen. Then he inks in the other lines and the words with a variety of heavier pens. Large areas of black are filled in with a brush.

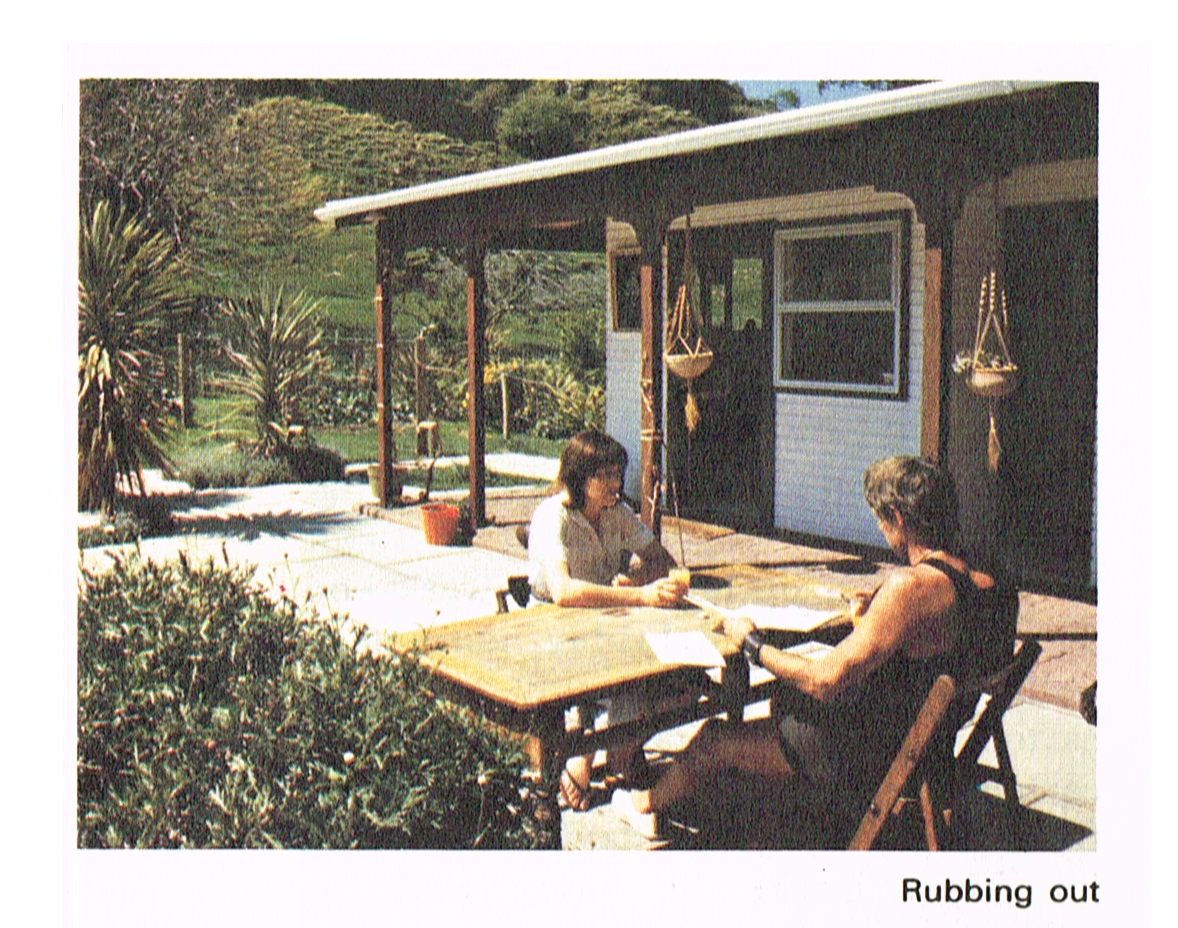

After about an hour and a half, he's finished all he will do to the cartoon that day. It still has pencil lines all over it, but he will tidy it up later in the week—on Thursday night and Friday morning.

In the meantime, Murray puts that cartoon aside, and starts on his second cartoon before breakfast. He wants to get three done, as well as having two times for ideas before he stops work at 1.30 p.m.

By then he is so tired, he just falls into bed and sleeps for a couple of hours. He won't wake up until his children come home from school.

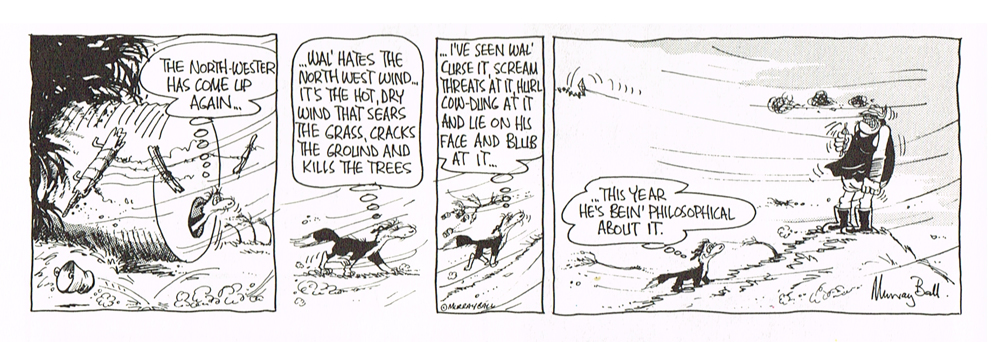

Then the day is his own—for spending with the children, looking after his animals and trees, and doing whatever he wants to.

On Thursday night and Friday morning, he will rub out all the pencil lines on these cartoons, and the rest of the cartoons he's done that week. Pam, his wife, will check the words for spelling mistakes, and they will both make sure they can't see any other mistakes or gaps in the cartoons. Then all the cartoons will be finished and ready for the printer.

On the land

Murray spends most of his spare time, in the afternoons and on Sundays, working around his land. He has almost two hectares, a few kilometres out of Gisborne.

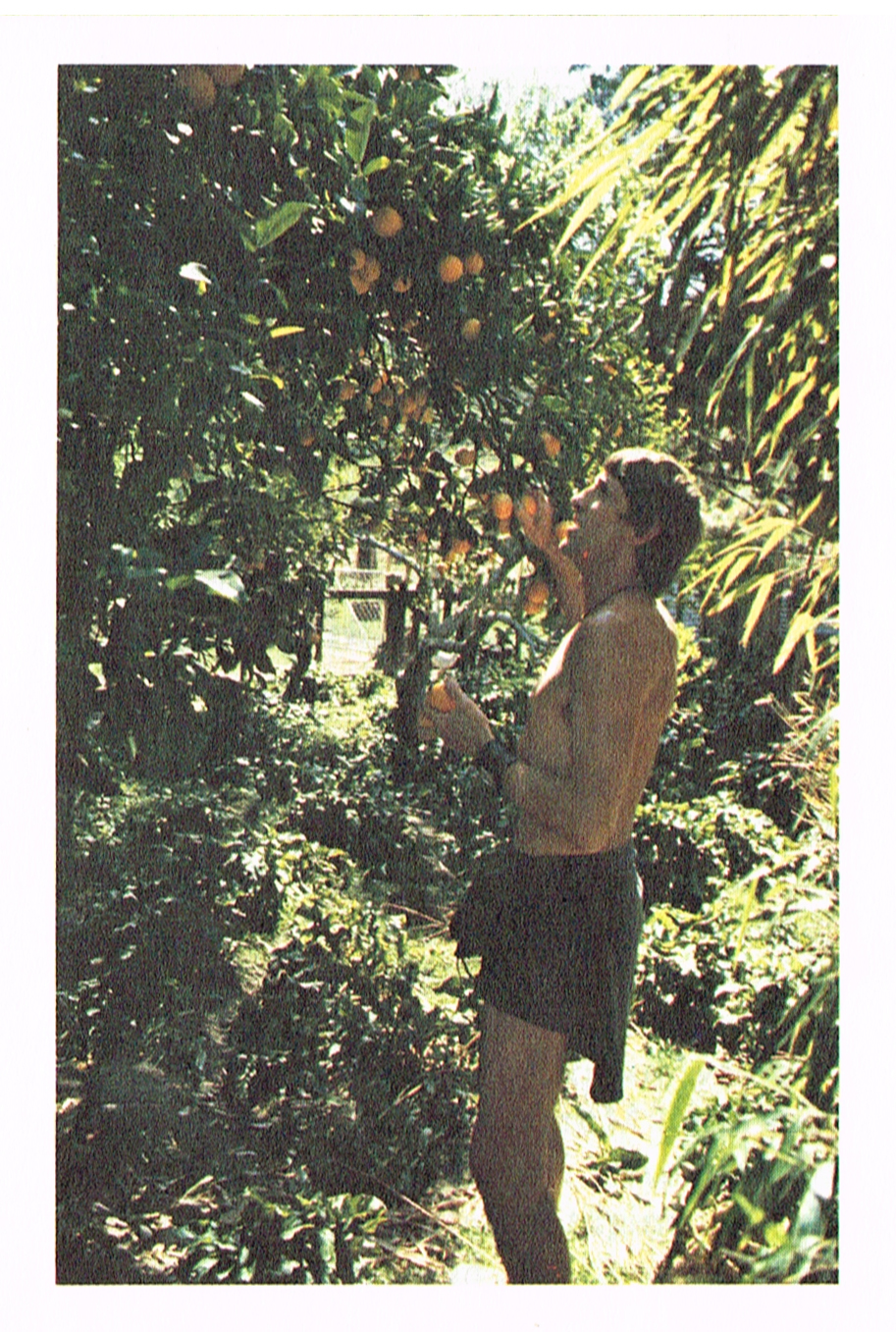

He has one cow, four ewes, a ram, four cats, twenty-four hens, two roosters, a bantam hen and some chickens, five geese, and half shares in two weaner pigs. He used to have a goat until it knocked him over and he decided it was time to sell it.

Murray's home is not Footrot Flats. He has put some parts of his place, such as the milking shed, into the cartoons. But other parts of the cartoons come from the farms of relatives and friends all over the North Island. He has put them together in his mind to make a new place.

Not many of the Footrot Flats characters are to be found at Murray's home. There are the background characters, such as the cow and the geese. But the only main character who lives there is Horse, the cat. He is a stray who stalked out of the bushes one day, and has dominated the other cats and most of the other animals ever since. ',"He's as big as a horse," said one of the children, and the name stuck.) Murray says Horse forced his way into the cartoon strip just as he forces his way in everywhere.

But there is no dog at Murray's house. Murray says the dog is like a part of himself, as most of the other characters of Footrot Flats are. The dog is like one of the best parts of himself, while Wal and Aunt Dolly have some of his worst qualities. The dog is also a bit like a dog Murray had for about fourteen years, from the time he was eleven. This dog was very clever, and used to climb trees, and open and close doors for Murray. And the dog is also like all New Zealand sheep dogs, which Murray thinks are amazing animals.

"They run about with their tongues hanging out and their eyes full of love for the farmer, and the farmer hardly ever looks at them. There is a strong bond between man and dog. But the dog shows his feelings for the man, and the man doesn't show his feelings for the dog. And yet the man is so dependent on the dog. If farming is the backbone of the country, the dog is the backbone of farming. They are superb animals."

Murray himself isn't like Wal in the way he regards his land and animals. He takes great joy in the animals and watching them grow. He says, "I can't ever get over the wonder of a cow. She could run you through with a horn—no trouble at all—but she just stands there while you take from her a bucket of milk, which will supply you with cream and butter and cheese and yoghurt. And she has a calf which she lets you take—all just for being allowed to stand there in your backyard and eat your grass."

That may sound a bit like Gooch. But if a cow happens to get through a fence, and into Murray's young nut trees, he will run after it and feel like killing it, just as Wal might.

The world of Footrot Flats and its characters are all figments of Murray Ball's imagination. But the fact that he lives in a place where the same sorts of things happen—lambing, and straying cows, and problems with fence posts—helps to keep the world of the cartoon strip alive and real. Everything that happens to Murray Ball enriches the world of Footrot Flats when he decides to visit it.

Photographs by Trevor Hyde

Copyright 2015 text Jane Thompsen, drawings Murray Ball, photographs Trevor Hyde.

Paper Trail

I like these portraits by Jem Yoshioka using The National Library’s heritage palette collection.

A Comic Bastard reviews Andrez Bergen and Matt Kyme's Tales to Astonish #3.

Caitlin Major at Hopscotch Friday.

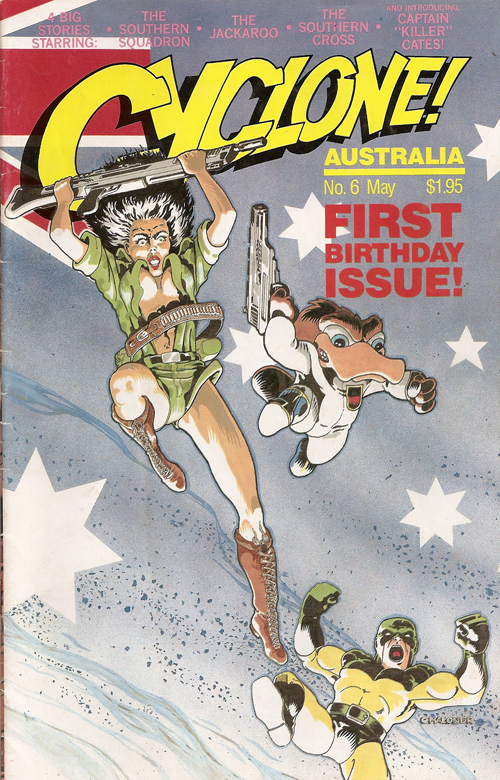

Pre-order Maralinga Book One - available in September.

Roger Langridge and Michael Faber ask "What would happen if David Cameron and Barack Obama met at a comics shop?"

It's two years old but I hadn't seen this interview with Dave de Vries before.

Paper Trail masthead by Toby Morris.